Jump to Episode: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

Noise filled the canteen. Knives, forks, spoons, cups and plates were being thrown into dishwashing machines or taken out of them, chinking against each other and being wheeled around the kitchen on trolleys. The loud sizzle of frying breakfasts and the shouts of the arriving day shift ordering food added appetising smells to the noise.

Ellis, Professor Ellis, looked as though he was in his mid fifties, and was dressed from head to foot in black overalls emblazoned Sunlight. Escorted by the standard issue personnel officer and carrying a plate of hot breakfast, the twenty year old trainee arrived, looking out of place in a charcoal grey suit, Bengal striped shirt and Miró tie. He sat opposite Ellis. The personnel officer said, ‘Morning, Professor Ellis. This is Theodore Williams,’ and disappeared.

The canteen supervisor had kindly scrawled ‘Reserved’ on the formica™ table-top with a marker pen. Ellis was close to finishing his bacon and eggs. The new arrival put his plate onto the table and began eating.

‘Welcome to The Works,’ Ellis began. ‘I suppose I should begin by apologising for the noise in here, but firstly it’s the only place for several miles in any direction where you can get breakfast without cooking it yourself, and secondly, the noise is so loud that we’re unlikely to be overheard.’

‘It’s a very good breakfast, sir.’

‘Don’t call me sir,’ said Ellis, ‘I insist. It’s Professor Ellis. Most important things first: have they offered you a decent salary?’

‘More than decent, Professor. I was surprised…’

‘Then you’ll pay for your own breakfast tomorrow. Bring a credit card or something because they don’t understand about money.’ The Professor paused for a second and sighed. ‘How simple life used to be when you carried money around with you and you bought things with it. So, I’m Professor Ellis and you’re Williams, have I got the right name there?’

‘Yes, Professor. Theodore Williams. Theodore Williams BSc, I suppose.’

‘And you’re the new hire.’

‘Yes, Professor.’

‘What in God’s name made you want to work for Sunlight? Most of the guys you’ll meet today are probably trying to get paroled out of Sunlight.’

‘Someone at Sunlight wrote to the head of the maths department and he recommended me. Jobs are hard to come by— I mean, I want to work for a socially conscientious small business with potential for growth that offers a realistic prospect of promotion and at the same time respects my interests and abilities and puts them to good use. And of course Rosentyre

| Maps of Rosentyre |

‘Spoken like a true Dalek. You’ve spent hours rehearsing that speech, haven’t you?’

‘Yes, Professor. I mean, no, Professor. I mean—’

‘Don’t be too modest. You showed imagination, persistence and fortitude, you anticipated a hard question and you prepared for it, and you didn’t even have the job when you wrote your answer. Why do you think Sunlight chose you?’

‘I’d like to pretend that I had no idea to what I owe the honour of being offered the chance to work here, but someone probably noticed that I got a first class degree in maths, my father went to Chamberlain School and both my parents voted Conservative.’

‘You’re completely right. I wrote to him. Your former Headmaster and I were at St Hubert’s University together.’ Professor Ellis paused and looked serious. ‘Well, here’s your first lesson. Your name is Horatio, your name is not Williams. As long as you are on Sunlight premises, talking to anyone about Sunlight or speaking to customers on Sunlight business, your name is Horatio. Horatio because it begins with H and the last person we hired got the G. You never use your real name even if your mother phones you at work. What do you think…’

‘May I change the name, Professor? It’s a bit nineteenth-century Admiral of the Fleet, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know. Have they given you your identity card yet?’

‘Yes, Professor. Here, I’m wearing it already.’

‘Oh, so you are. Then you can change your name when your card expires, not before.’

Ellis looked up at the clock. Eight twenty-five.

‘You’d best finish your breakfast because we have to go and watch an important event at eight thirty-eight and it’s downstairs at the other end of the corridor. While you eat, I’ll get the formalities out of the way.

You are now a member of staff at Sunlight. This place is governed by the State Secrets Act. You never talk about your work except to people — like him, over there — wearing Sunlight overalls and with a Sunlight identity card.’

‘Who is that over there? Anyone I should try to curry favour with?’

‘He’s Dr Paul Eaks, brilliant genetic engineer. Developed the Eaks Test for… some disease or other. But as there are only eight scientific practitioners in the entire company, including you, you’re bound to meet him sooner or later.’

‘Panic instability,’ said Horatio.

‘What?’

‘Panic instability. The disease that the Eaks Test detects. Runs in families. Mental illness, rare but crippling.

Sandeep Tolhurst

suffered from it and ended up in—’

‘Well, you can talk about that to Eaks, but if anyone else asks, Sunlight is a nineteenth century Quaker business that makes horse shoes, harrows and ploughs. Your job is to put our products into cardboard cartons, carry them to the Post Office and send them to all those steaming jungles and frozen wastes where the British Empire used to be. What you see and hear and smell and read while you’re here stays with you and you alone. No photography, no drawings, no maps, no phones except the one that we issue to you, no using the public internet, any notes you take stay in this building, and

| This building does not exist |

‘What? How can our colleagues send us postcards while they’re on holiday in Spain in the summer?’

‘That’s no great problem,’ said Ellis, ‘They address them to the Sunlight Traditional Farm Implement Company on Oxygen Street, Edinburgh, it’s a trap street. Now, back to what matters. Have you had enough to eat?’

‘Yes, thank you.’ Horatio wiped the grease off his lips with the paper napkin, dropped it onto the table and stood up, ready to go.

‘Come with me, then. Have you been given an idea of what Sunlight does?’

‘No, sir.’ Ellis glared at him. ‘I mean, no, Professor. Sorry. Only that they do advanced—’

‘You are forgiven this time. I worked damned hard for my title and you will use it. Now, come along, our demonstration will not wait. We’re going downstairs, on the double.’

Ellis and Horatio left the canteen, walked along the corridor of grey walls, rooflights and anonymous brushed steel doors, until they reached an electric gate. Specific authorisation required for entry. The gate opened ahead of them and closed after them. Down one floor in a lift, then along another corridor was another gate, and this time it didn’t open.

‘Who’s there?’ asked a loudspeaker at head height.

‘Is that you, Gresham?’

‘Yes, it’s me, Professor. I see you’ve got someone with you.’

‘Horatio, he’s the new hire. I’ve got his authorisation—’

The gate opened.

‘Thanks.’

Ellis and Horatio walked into a large, low ceilinged room with powerful forced air ventilation making a continuous hiss and half the room freezing cold. There were six chairs in a half circle, each placed behind a desk and a screen. Five of the chairs were occupied by men in black Sunlight overalls, which made them look like identical quintuplets. The computer displays were more varied than the people. In front of the half circle of desks, two straight yellow lines were painted on the floor about three feet apart. The yellow lines led from a roll-up door on the left to another roll-up door on the right. Both doors were rolled down, closed. No Exit.

‘Are these people clones?’ Horatio whispered to Ellis.

‘No, of course not.’ Ellis spoke normally, as though the question was nothing out of the ordinary and everybody asked it sooner or later. He gestured toward the empty chair. ‘You can have my seat, Horatio. You’ll probably need it and I need the exercise.’

One of the overalls spoke with neither emotion nor interest. Horatio thought it was the one on the right, but he wasn’t sure. They all looked the same.

‘Eight thirty-four and… three seconds, and all’s well.’

A second overall added, in the same flat tone of voice, ‘Vital signs, heart, respiration, blood pressure all on target.’

The first overall spoke to the microphone on his desk. ‘Send the patient in. Stand away from the yellow lines.’

Someone said, ‘Why do you always say that?’

‘Because it’s in the script. Gas masks on.’

Horatio turned anxiously to the Professor. ‘Where’s my gas mask?’

‘There aren’t any. He’s having a joke.’

The left hand roll-up door lifted and, almost silently, a lidless plywood coffin rolled in, apparently under its own power, between the yellow lines. Inside the coffin lay a man, wearing a hospital gown, skeletally thin, several teeth missing, covered in bruises and bleeding heavily. There was a large and spreading blood stain on the gown. There was blood oozing from his mouth and nose, and some stinking mess on the floor of the coffin.

‘What the devil happened to him, Professor?’ Horatio asked Ellis.

‘Virus infection.’

‘Are we all going to catch it?’

‘No, Horatio, don’t worry, you can’t catch it and neither can anybody else.’

The tortured soul in the coffin moaned weakly.

‘Are we going to cure him?’ Horatio asked.

Professor Ellis thought about that, and eventually he said ‘Yes, in a manner of speaking.’

First Overall spoke to the computer again, ‘Patient number one-two-two, Avner Gilbert, 48 year old male.’

On First Overall’s desk, the computer started beeping out the heart rate of the patient. First Overall spoke to nobody in particular, ‘When was this guy infected?’

‘Midnight yesterday, Gresham.’

‘Isn’t that a bit late to wake the medics up?’

‘Yes. But it means we don’t have to do take-away sums to work out the time elapsed to—’

‘Does anyone want a chip? Are you a bit peckish, Gresham?’ One of the overalls was unwrapping the newspaper from a pile of chips.

‘No thanks, Falstaff. I have to concentrate for the next couple of minutes.’

‘I missed breakfast, Falstaff,’ said another. ‘I’ll take one.’

‘Here you are, Digger. Catch!’ Falstaff took a chip out of the newspaper and threw it to his hungry colleague.

‘Thanks… Oh, God, it’s got brown sauce on it.’

‘Then you’ll have to get WFK in to clean the keyboard, Digger, like I do. They’re good at it, and it’s what we pay them for. Trust you to—’

‘Who’s WFK?’ asked Horatio.

‘We Fix Keyboards. Little Polish techno shop in the town,’ Ellis told him.

Falstaff announced expressionlessly, ‘Sorry to interrupt, boys, but it’s eight thirty-five and five seconds, and the BP is dropping.’

The pulse beeps stopped for a couple of seconds and resumed.

‘Heart is slowing,’ said Falstaff.

Digger read out, ‘Heart 49, pulse intermittent, respiration shallow, BP sixty on forty one.’

A moan came from the plywood coffin. Blood was welling up in the patient’s eyes and under his finger nails.

‘Give us another chip,’ said Digger.

‘Sure. Shall I lick the brown sauce off first?’

‘No, thanks. I can cope with it.’

‘Catch!’ The chip flew across the room. Digger reached up for it, but missed. The chip ricocheted off his fingers and landed in the coffin. The patient did not notice it.

‘Wide! No ball!’ cried Ellis, holding his arms out sideways.

‘Do you want a chip?’

‘No, thanks. I just had breakfast.’

Horatio told Professor Ellis that he was feeling a bit queasy, and the Professor replied that everybody did, the first couple of times they watched it happen, without mentioning what it was.

‘Are you sure I’m not about to catch whatever he’s suffering from?’ asked Horatio.

‘I thought that might be on your mind,’ said Ellis. ‘Yes, I am sure. No, you can’t catch it. It won’t affect you or anyone else.’

Falstaff spoke. ‘Sorry, guys, I forgot to watch the clock. It is now eight thirty-seven and forty-five seconds. Quiet, please.’

The room fell silent apart from the newspaper rustling and Horatio retching and the ventilator hissing and the patient moaning and making a last feeble effort to lie in a comfortable position.

‘Have this newspaper,’ said Falstaff, holding it out to Horatio. ‘Sorry, I’ve eaten all the chips.’

Falstaff led the chant, and apart from Horatio, the rest joined in, in unison.

‘Ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five…’

‘Are you feeling all right?’ Ellis asked Horatio.

‘Four, three, two…’

‘No, I feel sick.’

‘One.’

The irregular pulse beep stopped and a high pitched, continuous note replaced it.

‘Zero.’

Meeeeeep!

The patient spluttered and fell into an awkward position, his head twisted at an impossible angle, eyes open, tongue lolling out. Apart from Horatio, who was now sitting bent forwards, vomiting into the newspaper in his lap, everyone clapped, cheered and congratulated each other.

‘Flat-line,’ said Gresham, raising his voice to be heard over the hubbub.‘The patient has flat-lined.’

‘Flat-line at eight thirty-eight and zero seconds,’ said Falstaff.

‘Another triumph for British engineering,’ cried Digger.

‘Welcome to Sunlight, Horatio,’ said Falstaff, as the roll-up door on the right side opened and the coffin rolled through it out of the room. ‘Have a nice career.’

Theo

had been working at Sunlight for a bit over three weeks. They gave him something harmless to do, he did it, and everyone told him — correctly — that he was doing it well. He took the Scottish Public Holiday long week-end off, mainly to reassure his mother Margaret that the job he had accepted really existed, he was not sleeping freezing cold under a bridge in constant terror of the bailiffs and without enough money for the train fare home, and nor had he starved to death due to living by himself and not knowing how or where to buy food.

Slipping away early and unremarked from The Works on the Friday, he managed to arrive at his family’s large and nearly empty house in Craigkeld a few minutes before midnight. His mum had plainly already gone to bed. She was barefoot and wearing her dressing gown when she opened the front door.

‘Theo!’ she beamed at him. ‘At last. I thought you’d missed the train. Come in, come in.’ She thought for a second and added, ‘I’m overjoyed to see you.’

‘Why’s that? Has everything been all right?’

‘Oh, yes, absolutely. It was just so late that I thought you might have decided to travel tomorrow, or maybe you missed the train somewhere along the way.’

When Theo had been given the job and set off for Waverley Station a month earlier carrying a canvas sports bag of essentials, the house was exactly the same as it had been when Mum and Dad had first moved into it together in 1970 or thereabouts. Furniture, decorations, everything that they had bought for their house when they moved into it was still standing in the same place, and little had been added since. The dining room, with its carved table and matching chairs and hand painted crockery hung on the walls, far too big for one woman and her occasional visitor, looked as though for the whole month Mum had not so much as stood in it. Years ago the room had been arranged as if for an antique furniture catalogue and, apart from a couple of photographs of his father’s funeral, left undisturbed thereafter,.

‘The trains were on time, pretty much.’ Theo recounted the long journey. ‘It’s just a long way. The train that leaves Rosentyre at six doesn’t get to Edinburgh until eleven, and then…’

‘You must be very tired. I cooked sausage and mash earlier but it was so late that I ate my share and then I left the rest to cool. It’s still on the stove if you want some.’

‘Yes, please. I haven’t eaten since lunch time.’

‘Well, I can heat it up, I suppose.’

‘Don’t bother. I can eat it cold.’

Margaret brought a plate laden with cold dinner out of the kitchen, set it in front of her son with a knife and fork, and watched him start to eat.

‘It’s not much,’ Margaret said, apologetically, ‘but as it’s so late…’

‘It’s my favourite, and they almost never cook it in the canteen.’

‘What’s the food like?’ Margaret asked.

‘Not bad, considering.’ Theo thought about the canteen food. ‘They make us a cheap cooked breakfast, lunch and a hot dinner in the evening. If you live alone it’s a lot less trouble than cooking for yourself.’

‘You haven’t found a girlfriend yet?’ Margaret drew the obvious conclusion.

‘ ’Fraid not, mum. I’m signed up to this internet thing.

Medjool Dates. You never know.’

‘How much did that cost you?’

‘Thirty quid a month.’

‘And how many women have you…’

‘I’ve had three phone calls.’

‘I know a waste of time and money when I hear about one.’ Margaret dismissed Medjool Dates with blistering scepticism. ‘Go to Church and look. All the lonely women go to Church. They think God can’t be bothered sending them a husband and if they don’t suck up to Him, they’ll wake up one morning and realise they’ve turned into creaking elderly spinsters with grey hair and walking sticks. You don’t want to be all alone for the rest of your life, now.’

‘I hadn’t thought of that. I did think of launderettes and art galleries, but there aren’t any.’

‘How do you manage without a launderette?’

‘I got a second-hand washing machine. It works most of the time, I’ve only had the repair-man in twice. Anyway, I can hardly tell my date that the reason I’m trying to find a girlfriend is because I haven’t got a washing machine, can I?’

‘No,’ said Margaret after careful consideration. ‘You’ll need to get your story straight. “I need an angel to brighten up my dull and aimless existence.” Girls love that sort of nonsense.’

Theo had eaten everything on his plate.

‘Your room’s just how you left it,’ said Margaret. ‘By the way, how’s the job?’

‘It’s all right. I’ve not got any life altering decisions to take, or anything. I’m not supposed to talk about what I do…’

‘That’s the management fad of the week, is it? Make them keep everything a secret and they’ll work more for less wages, is that it?’

‘Well, Mum, it breaks no secrets to tell you that they knew I was a mathematician so they put me onto estimating demand. For the last three weeks I’ve been trying to work out how to predict the number of customers who’ll come knocking on the door, if they can find it, and how much money they’ll spend when they do. I told them to buy me a crystal ball and ask that, but they said no, we want to get accurate predictions without crossing any palms with any more silver than we already do. So after a Fourier analysis that fills more paper than the Scottish Daily does in a week, I’ve got half a dozen relevant correlations and some seasonal cycles—’

‘That’s further above my head than a flight to Bermuda,’ said Margaret, ‘and I need my sleep, I’m afraid. I’m really pleased that you’ve found a niche for yourself. Good-night, see you tomorrow.’

Theo awoke while it was still dark. The room was silent, for the clanks and hoots of Rosentyre Harbour were many miles away. He thought for a few seconds that he heard voices, but then realised that his mother was lying in bed listening to her radio, or more likely she had fallen asleep without first turning the radio off. He lay still for a while and then realised that as long as the radio was playing, he wouldn’t get another wink of sleep. Late night radio presenters were expert at keeping their listeners awake. The jingles, the shouts of feigned surprise and well rehearsed delight, the hoots of laughter, the forty year old pop records, the sound effects, the scripted phone calls, were all added to the waffle in carefully measured numbers like currants to a fruit cake, one every eight minutes, just enough to keep sleepy listeners awake.

‘Mum?’ he whispered as he tip-toed into her bedroom, not wanting to wake her if she was asleep.

‘It’s all right, I’m awake.’

‘Can you not sleep?’

‘Something’s keeping me awake,’ she said. ‘You’re troubled. I can tell. There’s something not quite right about the job, isn’t there.’

‘Mum, I could tell you but then I’d have to kill you.’

‘Ah, you’re a good man but you’re no Tom Cruise. So there is something. Do you want to throw the job in and come home? Everybody makes false starts sometimes — look at me, for instance. You’d be welcome to come and live here, you know.’

Theo found the prospect of living at home with someone he had known and loved all his life in the town he had known and loved all his life more attractive than it had appeared when he was actually living there.

‘What would we live on?’ he asked.

‘I’ve still got my lifelong annuity, my works pension, the state pension if I’m desperate, and you’ll get some

Nash,

I expect.’

‘We can live on that if we both stop eating.’

‘Don’t sneer too loudly. Your grandfather was a good and generous man. So why do you stay at… wherever you are? Sunlight?’

‘Mum, I don’t want to sound more exasperated than I really am, but you do realise my job, and everything connected with it, is top secret?’

‘Guessing how many customers will come into a farrier’s shop is top secret? Pull the other one.’

‘It’s the truth. I really have been asked to estimate future sales. But what worries me…’

Theo tailed off.

‘Yes? You don’t think I sat up until this hour for to listen to Moss and Myra’s Late Night Lorry Driver Sing-Along, did you? Can a horse-shoe factory afford a sales estimate from a St Hubert’s graduate mathematician, even if it needed one? Come on, I’ve let this banal drivel keep me awake all night in order to hear this.’

‘I’ve seen them removing dead bodies from the stock yard.’

‘Well, there’s a thing. Thanks for telling me. Shall I go to sleep now or will you—’

‘That’s all I know. There isn’t much more I could tell you. I don’t know what they’re doing and I don’t know how deep in the mire I already am.’

On

the other side of the street from the railway station,

in the middle of Rosentyre stood the village’s finest pub, The King’s Unicorn.

The building dated back to some year in the nineteenth century, at which time it was called

The King’s Field

and it served cheap beer, blended whisky, smoked fish and hot beef stew with dumplings to a small clientele of porters, shunters, engine drivers, ticket collectors and train passengers.

The pub had now, as they say, been re-imagined, refurbished, given a new name, roof, central heating system and sign on the street outside.

Theodore alighted from the last train of the day, dragging his suitcase packed with things he needed, like socks and a bottle opener, and things his Mum wanted him to have just in case, like window cleaning fluid. Eternally a train-spotter, he stood mesmerised on the platform and watched the signal turn green, the carriage doors hiss shut and the red tail lights of the train shrink into the distance and disappear around a curve. Theo left the station as someone was switching off the lights.

Many years of watching television programmes had convinced Theo that in a small town the only way to become accepted, to hear people say Good Morning to him as they passed him in the street, or to lend him a couple of teaspoons of Nescafé if he ran out of it, was to drink in the same public house as everyone else, and that was the King’s Unicorn, opposite the station entrance.

Standing on the street in the evening chill, Theodore steeled himself to deal with the hostile reception which he thought probably awaited every newcomer. This was the only way to become a full member of the village in good standing, rather than a foreigner and an intruder. He took a deep breath, opened the heavy hardwood door, hoped that the first time would be the worst and walked gingerly into the bar.

The room was large, warm, light, and full of people without being crowded.

The people did not look in his direction, hold its collective breath and fall silent. No fights broke out. Nobody yelled abuse at him. The conversations continued, in the corner two old men carried on playing draughts, and the barman pulled pints.

‘What may I get you, sir?’

‘Brown ale, please.’

The barman put a bottle and a glass in front of Theo and nipped the cap off the bottle.

‘Two pounds ninety.’

Theodore poured the beer into the glass and carried it over to a bookcase at the side of the room, where a handwritten notice read, ‘Please take a book.’

As he looked along the shelves,

‘The Ebony Mirror,’

‘His and Her Rules,’

‘The Mathematics of Guesswork,’

‘Leviathan Among the Seërs,’

‘Grasses and Crustaceans,’

he heard a Tyneside accent that he recognised saying, ‘Take the black one on the right.’

‘Gresham! What are you doing here?’

‘What am I doing here?’ Gresham was a short man, slender, darker skinned than many, the progeny of seven generations of coal miners and locomotive engineers. ‘I am steeling mysel’ for another week of stoking the refrigerators, shoein’ weasels, ploughin’ the marshmallow fields and gettin’ covered from head to foot in pig-swill. Such is the fate of yer lowly employee at the Sunlight Historic Agricultural Implement Company.’

Theo pointed to a well worn and

scruffy black paperback that looked as though it had passed through many hands. ‘Did you mean this book?’

‘Aye. That’n ’ll fascinate ye. I guarantee it.’

Theo pulled the book off the shelf. It did not look like a riveting read. ‘Why? It doesn’t look so interesting that I need to read it before anything else.’

‘Bring it ower here an’ come and sit wi’ me, Horatio. I hate drinkin’ alone, but if I stop, I won’t consume my recommended daily alcohol intake and then I’ll die of beer deficiency by about Wednesday. What are you doin’ here?’

‘Just back from spending the holiday week-end at my mum’s, and I’ve been on the train since lunch time.’

‘Well, now you’re back, and after you’ve taken a long swig of the brown ale, you ought to start reading that book, because the author was the drivin’ force behind—’

‘Hush! Don’t spoil the surprise, Gresham.’ Theodore settled down, opened the book and began to read.

Small scale warfare, the lessons of David and Goliath‘What’s this have to do with me?’ Theo asked.

By Prof Daniel Newman

‘Quite a lot. You’ll see.’

Chapter One: Strength is Weakness‘I think, on the whole,’ Theo ruminated, ‘I’d prefer to take home “Leviathan Among the Seërs.” ’It is said that someone once asked the great theoretical physicist Albert Einstein what weapons would be used to fight the Third World War. According to legend, he replied, ‘I know not with what weapons the Third World War will be fought, but the Fourth World War will be fought with sticks and stones.’ Einstein’s opinion was widely shared, although later commentators have cast doubt on the authenticity of the quotation.

‘If you work here for long enough, you’ll read it sooner or later. There’s little enough else to do here. An’ Leviathan Among the Seërs is tosh. By the same author that wrote The Prey with Two Faces.’

‘Gruesome. Thanks for warning me,’ Theo said, mentally adding that there was indeed nothing else to do if you didn’t count going to the pub and drinking.

‘Except go to the pub and drink,’ Gresham said out loud, ‘and you’re already doing that.’

Theo opened the paperback and read.

Before two atomic bombs were dropped, one on Hiroshima and the other on Nagasaki, the extent of the destruction which the bombs would wreak was universally under-estimated. In 1945, for instance, George Orwell, writing in an essay entitled You and the Atom Bomb, imagined an atomic bomb dropping on the Stock Exchange in London and life in the capital continuing as normal afterwards. Once two atomic bombs had been dropped, it became clear that the truth was much closer to that later envisaged by Douglas Adams. There was no conceivable consequence of not setting the bomb off that was worse than the known consequence of setting it off. In other words, the atomic bomb was a useless weapon. Despite the huge amounts spent on designing, developing and testing bigger and better atomic bombs, none has been dropped in anger since 1945. Two atomic explosions were sufficient to show that the bomb could never be used again.‘It’s my turn to buy the beers,’ said Gresham. ‘Another glass?’As soon as the military realised that atomic bombs powerful enough to devastate an entire city were useless in war, they asked the physicists to build a small atomic bomb. Their answer was not that for which they were hoping. It was No. You cannot build a small atomic bomb. You can only build a big one. The bomb must weigh at least the critical mass, or it will not explode.

The immediate consequence of this realisation…

‘I think I ought to be going home,’ Theo said after a little consideration. ‘I haven’t slept much.’

‘That’s a very sensible idea.’ Gresham upended his glass and drained it. ‘I’ll help with the suitcase. I can see it’s too heavy for you.’

‘Yes, please do, but I live on Nicholson Close, right across town.’

‘7 Nicholson Close, perhaps?’

‘Yes. How did you know?’

‘I stayed there too, when I first arrived. Mrs MacKechnie’s still going, then. Of course I’ll carry the suitcase. You carry the book and try not to get it wet.’

A quarter of an hour later, they arrived at 7 Nicholson Close.

‘Looks like she’s out.’ Theo made the observation first.

‘We can do as we like, then.’ Gresham followed Theo upstairs and lay the heavy suitcase down on the floor.

‘Mrs MacKechnie has a boyfriend, I think,’ said Theo, ‘She’s sometimes out until the small hours and I don’t think they have overnight lock-ins at the bingo hall.’

‘There isn’t a bingo hall,’ Gresham shook his right arm to get rid of the cramps. ‘And there isn’t a night shift at the fish factory, so it’s got to be the boyfriend.’

‘Lucky woman.’

There was a pause. ‘Mm.’ Gresham looked as though he might have been wrestling with a difficult decision.

‘Go ahead,’ said Theo. ‘Say it.’

‘All right, then. Have you ever had a boyfriend?’

‘Yes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| St Hubert’s University |

‘I did. That’s why I asked. I think I remembered there being a raid or something at St Hubert’s, years ago?’

‘2 am on Wednesday, 20 September 2013. I was lucky. I heard the noise and I hid. There were doors banging, dogs barking, shouts. They took a moment—’

‘Dogs barking?’ Gresham seemed surprised to hear about them. ‘Looking for drugs, were they?’

‘Yes, but none of us had any, but only because we didn’t know how to get them. Anyway, the Proctors took a little while to reach the room I was in. I clambered onto the top of the wardrobe and knelt there trying to be invisible. The man looked in the wardrobe but he didn’t look up.’

‘You’re joking. You got away with it, as easy as that?’

‘No, it works. Psychology 101. People don’t look up when they’re searching for something, that’s why you can hide up trees. The room was dark. The guy got the door open, turned the light on, glanced around, opened the wardrobe and shut it again, looked under the bed, said sorry and shut the door behind him. I climbed back down and turned the light off. Mr Beattie was embarrassed but apart from that, he had a lucky escape. They didn’t have anything to arrest him for. He went back to sleep. I went back to halls after the noise died down. By the time I woke up, I’d missed a lecture and the newspapers were having a field day.’

Gresham drew breath. ‘Do you want to sleep together?’

‘I think that’s a marvellous idea. Yes, when I’ve had a bath and relaxed.’

‘Bring on the bubble bath!’

‘It’s in the blue bottle. I need lashings of it. All that talk about the raid made me nervous.’

‘Don’t worry. They don’t go out on midnight raids here.’

‘That’s a great relief,’ said Theo. ‘The funny thing is, the man stank of aftershave and cigarette smoke. I swear I could see a faint trace of lipstick as well. He must have been as gay as a midsummer may-pole.’

Horatio stood nervously at the table in the small meeting room upstairs in The Works, in front of Ellis, whom he knew, Gresham, whom he had fallen three quarters of the way in love with, and two men whom Horatio did not recognise. The one looked around mid-career age and his name badge read Earle (Medicine,) and the other was around the same age as Horatio and his name was Dustan (Admin.)

‘Th- Thanks for coming,’ he began. ‘After a c- couple of weeks of number crunching, I’m in a position—’

‘I don’t know everyone here,’ said Ellis, who knew everyone. ‘Could we perhaps introduce ourselves? It won’t take a minute.’ Horatio was grateful to the Professor for easing the tension in the room. He realised that he had a small pile of name cards that he hadn’t given out and also that he hadn’t tested the projector. ‘I’m Professor Ellis. I’m an expert on viruses. Product development. Horatio, why don’t you go next?’

‘I’m Horatio, I’m the new boy. First in mathematics from St Hubert’s.’ He was still shaking slightly with stage fright. ‘I’ve spent my first month working on sales estimates. I had a crystal ball imported specially from ancient Rome and installed in my office. Drop by if you need a weather forecast.’ He turned to his friend. ‘Gresham, it’s your turn. You’re good at introducing yourself.’

A round of introductions was enough to relax Horatio a little, ‘I should have said thank you for coming. I appreciate being trusted to produce useful results. Given a choice between being useful and being interesting, most mathematicians prefer to be interesting.’

The attempt at witticism warmed the audience to him.

‘I’ll start with the important results and then I’ll tell you how I got them,’ Horatio continued. Dates and numbers appeared on the screen behind him. ‘It might take half an hour.’ Professor Ellis wrote the numbers down as Horatio continued, ‘These are the estimated sales volumes for the next six months.’

‘How accurate are these numbers?’ asked Falstaff.

‘Ten thousand dollars either way, I guess. Paradoxically, the smaller numbers have higher probability of errors than the big numbers. So you can see from the big numbers that our salaries are well provided for…’

The gentle laughter relaxed the meeting further.

‘…the company stays out of overdraft and we’re all on course for a massive Christmas bonus—’ and then there was a knock on the door. ‘Come in.’

The policewoman who walked in was young and obviously bewildered by the endless steel doors and warning notices. ‘Police.’

Nobody answered but, imbued with the secretiveness which is the fellow traveller of security, Horatio turned the projector off.

The policewoman looked around and asked, ‘Is there a Theodore Williams here?’

Horatio turned to the officer and said, ‘That’s me, Officer.’

‘You’re Theodore Williams?’

‘I am. But only in real life. Not in here. Inside this building, I’m Horatio.’

She held up her identity card. ‘I’m

W P C

Rayner Shaw,’ she said, ‘from Dunnabeg police station. I need a word with you. Can we go and talk somewhere quiet?’

‘There’s a little store room next door,’ said Horatio. ‘I think my key opens it.’

Gresham asked, ‘Is everything all right?’

‘It probably is,’ Horatio answered, ‘but if I end up in prison, come and visit me.’

The store room door clunked open when it saw Horatio’s name badge. The room had obviously not been used for a while but, among the junk, Horatio found a brush and cleaned the dust off the two wooden chairs. Horatio and W P C Shaw sat down and he asked her the obvious question. ‘Pardon my asking, Officer, but what’s this about?’

‘I can’t find the stockyard,’ she said in a whisper, as though she were embarrassed about not being able to find it. ‘Where’s the stockyard?’

It was Horatio’s turn to be bewildered. ‘There isn’t a stockyard. Deliveries come to the front door. There’s nothing stored outside this building. At the front it faces the road and at the back there’s a little flower garden.’

‘We’ve had a report of a dead body in the stockyard here. Do you know anything about it?’

‘It wasn’t me!’ Without thinking, and without any idea what Ms Shaw was talking about, Horatio added in rapid succession, ‘I didn’t do it. I wasn’t there. Nobody saw me do it. You can’t prove anything.’

Ms Shaw pretended not to be amused. ‘Mr Williams, you’re no Bart Simpson.’

‘Sorry. But if I’d known you were coming I’d have put the kettle on.’

Sigh. ‘Let’s for a moment pretend that we occupy the same universe.’ W P C Shaw had dealt with tiresome comedians before. ‘What did you mean when you told your mother that a dead body had been taken out of the stockyard? You did say that to her?’

Like a wicker basket of homing pigeons, the late night conversation with his Mum came back to him. ‘Oh,’ he said as realisation dawned. Horatio checked that the door was shut. ‘I didn’t think she’d tell anybody. Let me rattle you a yarn.’

They sat and stared at each other while Horatio wondered where to start his story. Ms Shaw broke the ice.

‘I’ve never seen so many security precautions in one place,’ said Ms Shaw, ‘and I’ve been on duty in

Bute House.

What on earth do you do here?’

‘I’m not allowed to talk about it. Besides, to tell the truth, I don’t know. I’ve been here a month and the only thing I’ve been allowed to do is slave over a hot calculator, a 2B pencil and two books about cyclic and progressive time sequences, with occasional breaks to go to the toilet, get a cup of tea and use the pencil sharpener.’

‘But you did tell your mother that there was something suspicious going on and it had to do with the stockyard?’

‘I did tell her that. She’d sensed that I was worried about something, and it was something to do with work. I said someone’d found a dead body in the stockyard. Truth is, I was worried about a mathematical problem that I didn’t have a solution for.’

‘Why didn’t you just say, “I’m stressed ’cause I can’t find a solution to a maths problem” ?’

‘Because then I would’ve had to explain the problem to her, and poor soul, she thinks mathematics is borrowing and paying back when you do a take-away sum.’

‘And the problem was what, exactly?’ W P C Shaw produced her notebook as if to write down Horatio’s answer.

‘Fourier analysis of approximate data. It doesn’t breach any secrets to say that I’m trying to predict future sales volumes from past data. Until I found a solution, the standard error of the predictions was too high by an order of magnitude. But Cooley and Tukey’s method runs into trouble, it gives wrong answers, when some of the data points—’

‘Okay. I get the idea,’ said Ms Shaw, although she didn’t. She put the pencil back into the clip on the notebook without writing anything. ‘I’ll tell the sergeant that there’s nothing to worry about and your Mum’s an old lady, easily confused and she might have dreamed the whole story. Don’t worry about it. I doubt you’ll hear any more of this.’

‘Pleased to hear it.’

Ms Shaw thought for a moment and added, ‘Just one other thing. Do all mathematicians talk like you?’

‘No. Most of us are like the famous piece of cod that passes all understanding. Thanks for helping to ease my mum’s worries. Can I do anything else to help?’

W P C Shaw looked at her wristwatch and answered, ‘Yes. I’ve got five minutes if you have.’

‘I think the crowd has picked its things up and gone home by now. I certainly have five minutes.’

‘I’ve never understood…’ Ms Shaw was trying to find the words for her question, ‘Can you show me how borrowing and paying back works when you do a take-away sum?’

An hour later, Horatio arranged a new time and place to announce the expected sales volumes, and he took Small Scale Warfare from his desk and opened it somewhere near the page where he left off.

Chapter Two: The Past is the FutureProfessor Ellis flung the office door open without knocking. He looked a little panicky and he appeared to have been running. ‘Horatio! Stop what you’re doing and come with me. We need you.’As Goliath learned to his cost, a stone, perhaps weighing one pound and neither explosive nor particularly dangerous, is a death dealing weapon in the right hands. Goliath’s adversary was David, armed with five stones, a sling and a sharp stick. David had spent the last several years as a shepherd and was used to killing wolves by flinging stones at them from the sling. Doubtless he had also honed his skill by taking pot shots at trees, rocks, tin cans, lemonade bottles, camels, greenhouses and policemen. Doubtless his skill was such that he could hit the head of a pin from a hundred yards away. David’s first slingshot knocked Goliath to the ground, and there David cut Goliath’s head off with the stick.

The development of more and more powerful explosives ended with the invention of the atomic bomb. The search turned instead to firing the old explosives, but more precisely.

It is now possible to guide a missile to Nº 5 Charlotte Square so accurately that the gunner can choose whether the missile should fly into the building through a window, fall down the chimney or knock on the door and ask whether the First Minister is at home—

‘First time for everything,’ said Horatio. Ellis glared at him. Horatio put the book down and stood up to leave. ‘What happened?’

They were rushing along the back corridor. ‘One of them survived.’

‘One of what?’ Horatio didn’t grasp the issue.

‘We’ve had a failure. You’re conducting the investigation.’

‘I’ll do my best, of course,’ Horatio said, with unusual diffidence.

‘Of course you will,’ said Ellis. ‘What do you think you’ll need?’

‘Well… a team of people who understand what the product does, how the product works, would be a good start. Medicine, virology…’

‘Who do you want on the team?’

‘I don’t really know anyone in the scientific team yet. I’d like to have Gresham with me. He keeps me grounded. Apart from him, well…’

‘Gresham. Good. Ask around the labs and put a team together as a matter of the utmost urgency,’ said Professor Ellis. ‘You’ll have all the budget you need.’

‘The first thing the team will need,’ Horatio scrabbled for ideas, ‘is all the test results of any kind relating to that patient and results of the same tests on a collection of patients on which the product, err—’

‘Data on a random selection of successes. Tell I T to give you database privileges and if they piss you about, ask them to talk to me about it. How many cases do you think you’ll need?’

‘To find outliers with a Z test, if there are any outliers? More the merrier but twenty ought to be enough.’

The electric gate at the end of the corridor opened, and Ellis ushered Horatio into the auditorium in which he had spent most of his first day at The Works.

‘Are you carrying your company ID?’

‘Yes, Professor, it’s in my shirt pocket.’

‘Good, you’ll need it because if you don’t have it, the doors won’t open and Security will appear from under a rock, like a shoal of piranhas. Now, watch this. This is live video.’ Ellis sat down at the nearest desk and the computer lit up. He typed something, and a video opened. They saw a man wearing an overcoat, carrying a bag of groceries and ambling down a shopping street. ‘See? That’s him, there, Patient one five five, Jory Hodgson, age forty-three.’

‘Looks like he’s out shopping,’ Horatio observed.

‘Crew member on the ferry. Lives on Sandpiper Terrace…’

‘I’d love to know where he found the money for a house there.’

Professor Ellis continued, ‘The house has four bedrooms and a garden the size of

Hampden Park.

He bought it with half a million pounds that he inherited from his grandparents, so choose your grandparents with care. Married to Bonny-Lee, two children, middle income, studied performing arts at Montrose, pollen allergy…’

Horatio stared at the video. ‘That’s the main street in Lochkeld, isn’t it, Professor. I recognise it. So what’s wrong with Mr Hodgson?’

‘Yes, it’s Lochkeld. The cameras identify themselves over here,’ he pointed, ‘Farmer’s Way, Lochkeld Nº 3. And what’s wrong with Jory Hodgson is, he’s alive. He should have been far too weak to stand up by now. Nothing’s happening to him. I need to know what we did wrong.’

‘So when do I start investigating?’

‘You’ve already started. Get everyone and everything together tomorrow morning. Make sure you check your e-mail because you’re running the show.’

‘Well, Professor, I’m touched by the faith you have in me, but—’

‘This is an emergency, Horatio. You are quite likely the best mathematician in Scotland. Find the problem, fix it, stop it happening again and you can bath in modesty later on.’

‘I fully intend to,’ said Horatio. ‘I shall be more modest than you or anyone else can imagine.’

‘One other thing,’ the Professor thought for a moment, ‘This is absolutely secret, at least until you’ve fixed the problem. Understand?’

‘Yes, Professor.’

‘Nobody’s going to buy a product that doesn’t work.’

If you believed the

street sign, the name of the street that ran beside Rosentyre harbour was Sràid a’Chladaich. The original name plate,

Shore Street,

had been painted over and later removed altogether by the fervent nationalists of the late nineteen-fifties. The County Council, probably wisely, had not replaced it, arguing that had the English language name plate been removed during the War, and the Gaelic one left in place, it would have been easy to catch German spies because they would have to ask which street they were on, or how to pronounce it, or pronounced it comically wrongly.

Actually, during the war the English language name plate had indeed been removed, and not a single German spy had been detained as a result. Somewhere there is the gun barrel of a Centurion tank or the fuselage of a Spitfire made in part from the melted down name plate that once gazed down upon Shore Street, Rosentyre.

Theodore was walking home. As he often did, he chose to go along Shore Street, beside the harbour, where he could look out to sea, watch the seagulls eating spilt curry and chips off the street, see the small boats in the harbour riding the waves, hear the bells of the boats, the waves breaking on the rocks, the honks of the birds and the rumble of occasional aeroplanes departing Inverness Airport on the opposite side of the firth. He watched for the small passenger ferry that sailed every couple of hours from Rosentyre to Nairn, storms permitting. He thought of this way home as going the pretty way, walking for a quarter of an hour longer than necessary in exchange for the calm that the view of the harbour conferred upon his soul after a day of difficult work.

Rosentyre was far too far north to benefit much from tourist traffic, but the shopkeepers on

Shore Street (or Sràid a’Chladaich if you know how to say it) did their utmost to provide everything the tourists would have demanded, if there were any. There was an ice cream café, a fish and chip shop, a post office, a grocer, a herbalist who told fortunes as a side hustle, an expensive whisky off-licence, an Indian take-away and a sign pointing to the railway station.

Theodore was passing the post office when he heard the kerfuffle inside. He heard one voice, a male voice, cursing and hollering threats and another voice repeating ‘Don’t hurt us, don’t hurt us.’ The door flew open and a young man ran out. He was unshaven, untidy, wearing a black bomber jacket and leather jeans, and carrying a butcher’s knife in one hand and a pile of notes and coins in both.

Instinctively, Theodore stuck one foot out. The young man tripped over it and fell hard. Reaching out to try to stop himself falling, he cut his hand deeply and let go the knife. With the other hand he released a cloud of banknotes and a shower of coins to the four winds. He landed face down on the pavement shouting, ‘You’re dead, you bastard!’

The force of the collision knocked Theodore off balance. He stumbled and landed heavily on top of the thief just as he was trying to stand up and grab hold of the fluttering cloud of banknotes. Theodore managed to kneel on the small of the thief’s back and hold his wrists.

He heard applause from the Post Office clerks, a man and a woman, both in their fifties, who had spilled out onto the street, and cheers — ‘Well done, sir, well held’ — from a tourist in a Burberry overcoat and a sou’wester who had been standing looking out at the harbour and taking photographs with an impressive big, black and silver Leica.

‘Do you have your phone?’ said Male Post Office Clerk.

‘It’s in the shop,’ said Female Post Office Clerk. ‘I’ll dial nine-nine-nine.’

‘That won’t be necessary,’ said W P C Rayner Shaw. ‘I’m here already. Theodore! It’s all right, I’ll take over from here—’

‘Pig! Bloody pig!’ came a shout from the felled man.

‘Hamish Todd,’ said Ms Shaw as she grabbed the thief’s arms and wrestled them into handcuffs. ‘I’d know that incoherent swearing anywhere. Now, you just lie still for a few minutes, and I’ll call for a van.’

As she found the mobile phone in a jacket pocket, she double checked, ‘That is you, Theodore, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Well spotted. How did you get here so quickly?’

‘I’ve been here for an hour or so. Coastguard reported two men acting suspiciously on the ferry pier, so I hitched a ride on a prison bus going to Inverness Airport. Turned out, the two men were civil engineers checking the stonework.’

The Post Office clerks said their thanks to W P C Shaw. They assured her that they would make witness statements in the next day or two and they didn’t need an ambulance, and they traipsed back into the Post Office and put the ‘Closed’ sign on the door. The photographer was nowhere to be seen.

‘You rode here in an empty seat on a bus-load of deportees?’ Theo asked. ‘That must’ve been more fun than calling a taxi.’

‘No,’ Ms Shaw shook her head, ‘it was half a dozen long sentences on an educational visit to Spain. Language, Landscape and Liquor,’ sort of thing, but not necessarily in that order. It keeps them out of trouble.’

‘Lucky sods!’ Hamish railed loudly, still face down on the pavement. ‘When’s this sodding van going to arrive? I’m getting goddamned mud up my nose.’

‘I quite forgot.’ Ms Shaw turned her attention to the matter in hand. ‘Mr Todd, do you want to be cautioned in English or Gaelic?’

‘You can pissin’ say it in Siamese, for all I bloody care,’ grunted Mr Todd.

Ms Shaw took a deep breath and recited in Siamese for half a minute or so.

‘That was an impressive performance,’ said Theo, open mouthed in astonishment. ‘I’m really grateful to you for turning up so promptly. I don’t think I could have held the man down for much longer.’

‘I’m impressed too.’ Ms Shaw admitted. ‘I’d never have guessed that I’d find you moonlighting as a

super-hero. Where are the bright red cape, the blue shirt and the red underpants?’

‘They don’t fit me any more.’ Theo explained. ‘I’ve lost weight.’

Blue lights flashing, a police car arrived and its driver helped Ms Shaw to stand Mr Todd on his feet — ‘Well. Hamish Todd. What a surprise.’ — and load him into the back seat of the car hollering ‘Pigs! Leave me alone, pigs!’ at the top of his voice. The car drove off, leaving Ms Shaw and Theo standing, laughing, on the pavement outside the Post Office.

‘On days like today,’ Theo surmised, ‘you must really enjoy your job.’

‘I’m not allowed to do this in uniform,’ Ms Shaw giggled. She took her peaked cap off and kissed Theo. ‘We both need to cool down. Fancy a cup of coffee and an ice cream? I’m buying.’

‘That’s a very kind invitation, Ms Shaw,’ said Theo, ‘and I’d love to.’

‘Rayner. You can call me Rayner, even if I put my cap back on.’

‘Where did you learn Siamese, Rayner?’ Theo asked as they waited for their order in the ice cream café.

‘I didn’t. I’m not entirely sure that Siamese is a language at all. I was just wiggling my tongue and singing “Roll Out the Barrel.” ’

The waitress, who was also the chef, the dish washer and the proprietor, brought two Viennese coffees on a tray along with two large glass dishes each holding a pint or so of ice cream covered with diced fruit.

‘I‘m glad it sounded convincing.’

‘Very convincing for a minute and a half of unrehearsed soliloquy, I’d say.’

‘Well, not quite unrehearsed,’ Rayner admitted, ‘I go to a Pentecostal church occasionally.’

‘Let me ask your opinion about something.’ Theo weighed his words and spoke with care. ‘You say that you occasionally go to Church. My Mum says I should go to Church to look for a girlfriend, because I haven’t got one. Do you think it’s a good idea?’

‘You never know who might come and sit beside you,’ said Rayner. ‘Come to think of it, I’ll be escorting the Revolt Party march tomorrow. If you want to talk to me about the Pentecostals, why don’t you join them? There won’t be any trouble, and you never know who you might meet.’

‘I’ve never really paid much attention to the Revolt Party. As they’re competing for my vote, I really ought to find out what they’ll do if they’re elected.’

‘The first thing they’ll need to do is to set light to the Lake of Fire again,’ Rayner predicted, ‘because Hell will have frozen over from bank to bank. Did you like the ice cream?’

‘Very good indeed.’

‘Well,’ said Rayner, ‘I have to pay the bill, put my cap back on and start wandering around the town again, telling people the time and the way to the Town Hall. I swear that half the people in this town have left their wristwatch at home. Tomorrow at six in the evening, come wind, rain, shine or earthquake, I have to be standing in the car park of the King’s Unicorn watching half a dozen wannabe kingpins mooch quietly around the town.’

‘Six o’clock at the King’s Unicorn,’ Theo repeated. ‘Don’t let them start the revolution without me. May I bring Lois Lane with me?’

‘No,’ said Rayner. ‘She might inhibit you.’

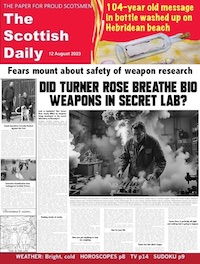

By the next morning, the only thing about the incident outside the Post Office that Horatio hadn’t forgotten about was that W P C Shaw had let him call her Rayner, bought him an ice cream and kissed him. It came, therefore, as a surprise when he saw The Scottish Daily which some helpful soul had put on his office desk. He was the lead story on the front page.

‘Have-a-go Hero foils knife raid,’ it read.

Yesterday must have been a slow news day. He imagined the editorial conference held just before midnight, choosing tomorrow’s front page lead from a small pile of stories off the wires.

Faced with the choice of (a) King stays in bed, (b) Delia Smith eats deep fried jam sandwich in Norwich, (c) All quiet on the eastern front and (d) Passer-by trips up robber in Scottish town that reader couldn’t find on a map at gunpoint, the trip hazard story would have been their automatic choice.

Horatio guessed with reasonable certainty who the tourist with the big camera worked for and what his job was.

He wondered whether it was worth trying to smuggle the paper out of the office and decided that the risk of being banged up for a breach of the State Secrets Act justified the small cost and big inconvenience of putting it in the waste paper basket, buying another copy in town and carrying it straight to a joiner who would frame it.

‘Sorry,’ ran the message that arrived in Horatio’s mail, ‘I haven’t found anyone else to help you investigate yesterday’s failure. You can work with Gresham for the moment so you’re not struggling on your own. Ellis.

‘I’m not much surprised,’ Horatio said out loud, ‘because that’s my job.’

‘P. S. Well done, O righter of wrongs and virtuous defender of the law-abiding citizen.’

Horatio realised that he had forgotten to ask Gresham his official issue phone number. There was no piece of paper bearing a list of names and numbers. Using the secure internal telephone directory was legendarily time consuming, especially considering that he could just go into the corridor and shout ‘Gresham!’ as loudly as he could, but sooner or later he would have to use the telephone and it would be as well not to put off finding out how it worked until he needed to fetch the Fire Brigade.

Horatio picked up the phone and an irritating synthesised female voice said ‘Name badge.’

‘What?’

‘Name badge.’

‘What do you want me to do?’ Horatio asked, knowing full well that the irritating voice would not tell him.

‘Name badge.’

‘This is getting me nowhere.’ You could only get away with speaking in such an excruciating voice, Horatio thought, if you were saying something that people wanted to hear, like

‘You are due a refund of income tax’

or

‘I have found your cat’

or

‘Nigel Farage has fallen down a hole.’

If you were saying something annoying—

The irritating voice said, ‘Time limit exceeded. Goodbye!’ and the phone stopped talking.

‘Hello? HELLO!’

The phone did not answer. Horatio hung up and glowered at it. ‘Bloody computers. They can’t do anything right.’

Gresham knocked on the door and walked in.

‘Hey, sweety pie, have you seen the papers?’

‘Yes. I’ve been elevated to the rank of Hero.’

‘In fact, I know you’ve seen the papers, because I bought two and I put one on your desk.’

‘It’s going to take me a lifetime to live this down. All I did was stand there while everything happened around me. Anyway, I’m glad you came along, because the phone didn’t let me ring you up. All the phone did was say “Name badge,” and then it cut me off.’

‘Oh, yes,’ Gresham explained, ‘you’ve got ten seconds to hold your name badge near the phone or it switches itself off. I had to work that out all by myself, you know.’

‘Your ability to talk to computers duly dazzles me. When you’ve done that, can you make a phone call?’

‘Yes. One phone call, then you have to start again.’

‘How I long for an ordinary phone so I can dial the number I want and, Bob’s your uncle, the person I want answers. Anyway, you and I’ve got some serious investigating to do. Where do you want to start?’

‘I’d say we should see what records and test results we have of this patient,’ said Gresham.

‘Jory Hodgson,’ Horatio put in, ‘His name’s Jory Hodgson.’

‘And we also need to gather some data on successes,’ said Gresham. ‘There are about a hundred, I think.’

‘I reckoned that twenty’d be enough to cast around for possible causes.’

‘Which means,’ Gresham said, ‘that we need to get some help out of I T. Not to mention some sense.’

‘This should be good,’ said Horatio. ‘I think I know where their office is. Come on.’

In the canteen at lunch time, Horatio chose chicken and Gresham chose fish. Tavin from I T had been more helpful than either had expected.

Gresham looked up and asked, ‘Where do we go from here?’

‘We sit and bash the data until we find some characteristic of Jory Hodgson that nobody else shares.’

‘Nobody else so far,’ said Gresham.

‘Well, yes, there’s always…’ He pointed to the sign. Do not discuss work. We aren’t allowed to talk about work in here.’

‘All right, then: Is the chicken nice?’

‘Not bad. This chicken must’ve been starving. Beats a Foodmaster Meal in a Box, all the same. What sort of fish is that?’

‘Fried fish,’ said Gresham. ‘Batter on the outside, fish on the inside, handful of chips.’

There was a pause.

‘You know,’ said Horatio, ‘the other thing I think we should get is a blood sample.’

‘What? Do you think this fish had some sort of disease?’

‘No.’ Horatio laughed. ‘I’m sure the fish is perfectly healthy, apart from being dead. I mean Jory Hodgson’s blood. We need a sample of Jory Hodgson’s blood for analysis, to see if there’s any sort of immune reaction or anything.’

‘Shall we sneak up on him with a cut-throat razor and a milk bottle? Like this.’ Gresham mimed sneaking up on what remained of his battered cod to the tune of the shark in Jaws and then stabbing it repeatedly with the point of his fish knife while mouthing the staccato violin shrieks from the stabbing scene in Psycho. ‘Der-dup, der-dup, der-der-der-dup, Eek, eek, eek, eek…’

‘That’s a brilliant idea but I think it needs a bit more tomato ketchup on it,’ said Horatio.

Back in his office, Horatio found himself devoid of ideas for drawing blood from Jory Hodgson without him noticing. Maybe Gresham would think of something. In the meanwhile, he picked up Small Scale Warfare once more, and carried on reading from where he left off.

Chapter Three: The Arrow is the TargetThe use of infectious diseases as weapons of war suffers similar limitations to the use of nuclear explosives. Its effects are too widespread and it kills the wrong people. In the Middle Ages, armies laying siege to a town fouled the drinking water by throwing animal carcasses into the wells. All the people of the town became too ill to fight, even though to force a surrender it was sufficient to force a handful of decision takers to surrender.

Is there an infectious disease which could stop an army? The British spread anthrax over Gruin-Árd island off the west coast of Scotland, killing every sheep there. The island was still uninhabitable fifty years after the event, and the British never used anthrax spores as a weapon.

Other diseases also became candidates for biological warfare. Yet the problem was not the lack of sufficiently lethal infectious diseases, but the same problem that had beset nuclear explosives. The diseases were so highly infectious and so lethal that they were useless as weapons of war. Killing one person whose death might improve the outcome of the war would likely entail killing hundreds of others whose deaths would serve no tactical purpose.

The hope for changing the nature of warfare comes from an obscure branch of genetic science. It is the simple observation that two patients may be exposed to the identical bacterium, or to the identical virus, or the identical prion, and one patient will have no symptoms while the other is severely affected, perhaps even killed by it. The difference between different patients’ vulnerability to an infection arises out of differences between the patients’ immune systems specified in the patients’ DNA.

Suddenly it was ten minutes past five, and the King’s Unicorn was half an hour distant.

Theodore couldn’t see Rayner. He looked around the car park and saw a young man standing on a box behind a Revolt Party poster. Vote Rose X, the poster read. Mr Rose was warming to his subject.

‘When you find rabbits in your cabbage patch, what do you do about them?’

Eight people stood in the car park, listening disconsolately to

Turner Rose, the man who was to be the Revolt Party candidate in the next election. They wore brown and black badges and they buttoned their coats and pulled their collars up to keep out the evening chill. It would have been hard, Theodore mused, to imagine a less revolutionary crowd, or a smaller one.

‘Do you welcome them, let them eat as much as they want, and build a luxury hutch with air conditioning and maid service to make sure that they enjoy their stay?’

The crowd shook their heads. They didn’t and they wouldn’t. A man in a grey overcoat ventured, ‘Shoot them,’ and a middle aged lady with ginger hair added, ‘Make them into a casserole with onions and carrots.’

‘Well, that’s a bit of an extreme remedy,’ said Mr Rose. ‘Perhaps—’

‘And a couple of tablespoons of peas,’ said a younger lady with a black and brown scarf.

‘No,’ said the overcoat. ‘Peas don’t go with rabbit. You could try tomato.’

‘A dash of worcester sauce might give it a bit more taste,’ said a young man whose black hair looked as though a bird had made his nest in it.

Realising too late that his chosen metaphor wasn’t evoking the imagery that he expected from his audience, Mr Rose tried to continue. ‘I mean, you don’t want to kill them, just to keep them out—’

‘No, you don’t,’ said the overcoat. ‘You’ve never so much as seen a rabbit, have you? You’ve got to shoot ’em. You can’t run after them with a catapult, grab ’em by the back legs and ping them away over the hills and into the Cromarty Firth. If you don’t shoot ’em, they’ll eat everythin’ in the entire allotment an’ then they’ll start on the plot next door to yours.’

‘I still say you should put peas in it,’ said the scarf. ‘Listen to authority. “No casserole can be considered complete unless it’s got peas in it.” It was Egon Ronay what said that, I think.’

‘Gordon Ramsay,’ said a man who looked about forty and wore a cricket club blazer. ‘I saw him sayin’ it on TV.’ He nodded sagely and went on, ‘Egon Ronay died in 2010.’

‘Well, he said it before he died,’ said the scarf.

‘Let me take a different example,’ Mr Rose began, but a cry of ‘Don’t change the subject’ from the overcoat un-nerved him.

‘This is as lively as I’ve ever seen them,’ said Rayner.

Theo jumped. He hadn’t noticed her in the crowd. ‘Hello! I wondered where you were.’

‘I was keeping an eye on things,’ she said, ‘and this is as lively as they’ve ever been, so I don’t think they’ll be marching around the town with blazing torches, smashing windows, setting fire to buildings and impaling one another on pitchforks.’

‘Let us march around the town,’ called Mr Rose, evidently having abandoned his speech for the evening, ‘chanting as always, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it any more!” ’

‘I’m as mad as a hatter, he means,’ Rayner muttered. ‘One seat on South Lanarkshire Council and he thinks he holds the world in thrall.’

‘I’m sure I’ve heard that mantra before somewhere,’ said Theo.

‘It’s not original,’ said Rayner, ‘but it’s rhythmic and it’s what they want people to hear.’

‘Forward together! Follow me!’ cried Mr Rose, leading the chant. ‘I’m as mad as hell…” ’

A light drizzle began. The small crowd took up the chant and began to amble gently down the road, looking mostly at their shoes and muttering, ’I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it any more!’ as if they didn’t want anyone to notice.

‘You and I,’ Rayner explained to Theo, ‘walk around after them, just in case all hell breaks loose.’

‘I don’t think it will.’

‘Neither do I, but it beats standing in the rain outside Bute House.’

‘You mean, you actually turned down the chance to stand in the rain outside Bute House in order to come here?’

‘Only because you were going to be here.’

‘That’s very kind. Did they give you a scarlet tunic and a bearskin hat?’

‘They’re safe in my locker in Dunnabeg,’ said Rayner, ‘beside the bagpipes.’

‘Do they suit you?’

‘Yes. Well, if they really existed, they would make me look like the

|

|

| Guardian of the Underworld |

Theodore walked back from the bar. He put the glass of amber wine onto the table in front of Rayner, stood the brown ale in front of his chair, and sat down.

‘Thanks,’ Rayner said. As she relaxed, a smile lit up her face.

They touched their glasses. ‘Cheers!’

‘So, Theo, now that you’ve trudged around town for half an hour in the company of the Revolt Party, what do you think of them?’

Walking around town in the drizzle, Theodore had been thinking more about whether the rain was going to become colder or heavier, and about whether Rayner would make time to have a drink together afterwards, and he hadn’t really thought about the Revolt Party. ‘They know how to make casseroles, they don’t know how to keep rabbits out of their cabbage patches, they think Egon Ronay was a controversial orator unless it was Gordon Ramsay, and… I guess… they’re as mad as hell and they’re not going to take it any more, but I don’t really know what “it” is, and I’m not sure I’d have noticed how angry they were about it if they hadn’t told me.’

Rayner sipped the wine. ‘Delicious. Now that really is something special.’

‘Malmsey. It’s a specialty here. Noah’s wife got herself so tanked up on it that Noah, Shem and Japheth had to carry her onto the Ark.’

‘Why didn’t they just put her onto a taxi?’

‘Because there weren’t any taxis back in those days,’ Theo explained, ‘only Arks. It tootled around the floodwater for forty days and eventually landed beside the kerb at Number Three Uruk Gardens, Gilgamesh, where the driver charged her fifteen bob for the ride and ten shillings extra for taking all her pets with her.‘

‘Plus the traditional fifteen per cent tip,’ Rayner added.

‘Making a total of £1 8s 9d,’ said Theodore before he could stop himself, still the mathematics graduate hours after the end of his shift.

’God’s truth!‘ Rayner was astonished. ’How did you do that?‘

‘I didn’t,’ said Theo. ‘I mean, I didn’t really do anything. I can see the numbers. They’re still there, in digits like the neon signs you see in hairdressers’ shop windows, except instead of “No appointment necessary,” it says “£1 8s 9d.” ’ He pointed at the invisible numerals in the empty space on the table, two feet in front of him, in between the beer mat and the bottle of brown ale. ‘Pound sign, one, eight, nine.’

‘There’s some dust floating in the air, sparkling a bit, but…’

‘It’s a gift,’ said Theo, ‘like other people see ghosts or unidentified flying objects or sure fire business opportunities. I’ve always had it.’

Rayner took a couple of deep breaths. ‘I’ve never come across anything like this. What happens if she pays the driver with a five pound note?’

‘£3 11s 3d change, and, yes, I can see it.’

‘And you could do that ever since your first day at school?’ Rayner asked.

‘I remember the boy who sat next to me asking me what the answer to some simple question was. Five plus four, that sort of thing, and I told him to read the question and write down the numbers that appeared in front of him. He had no idea what I was talking about. That was when I found out that nobody else could see them.’

‘What happened?’

‘The little bastard asked the teacher about the numbers that appeared in front of me, and they dragged me off for a drug test.’

The walkie-talkie in Rayner’s pocket began to squawk.

‘Is that you off somewhere?’ Theo asked, as she fumbled with the zippered pocket from which the squawks came.

Rayner pulled the walkie-talkie out of the pocket and held it without answering it. ‘I’m on duty until midnight,’ she told Theo. ‘Wait a second while I find out what sort of cataclysm is next in line for Superwoman and her beloved have-a-go caped crime fighter Batman.’ She pushed a button on the black box with her thumb, and the squawking stopped. ‘Shaw.’ she said, trying to sound professional.

‘Evening, Rayner. Sorry to call on you this late in the evening but I think you’re nearby. Damn it, I dropped the note…’

‘It’s probably on the floor somewhere, sir,’ she said.

‘Yes… Ah, here we are. Automatic alarm operating. Can you go and have a look? Paper Pusher, the newsagent on, er,’ he struggled with the pronunciation, ‘Sràid a’Chladaich. Is that -ch as in loch or itch?’

‘It rhymes with… Actually, I can’t think of anything. I’ll go straight away, sir.’

Rayner put the walkie-talkie down onto the table and turned to Theo. ‘Those damned alarms go off all the time. Fancy a short walk in the cold and dark? We can hold hands.’ She fumbled the radio into the zippered pocket and added, ‘If there’s anyone breaking in, no heroics. OK?’

An alarm bell was ringing loudly and a brilliant lamp was flashing above the doorway of Paper Pusher.

‘Oh, crikey, this is all I need.’ Rayner let go Theo’s hand, ‘Sorry, honey, you stay over here,’ and she walked up to the shabby youth who was standing in the shop doorway cursing and trying ineffectively to prise the lock open with a screwdriver. He might have been fourteen, she thought, or thirteen and on the tall side.

‘Why don’t you just ring the doorbell?’

‘ ’Cause there’s nobody in,’ he said, spinning around.

‘Give me the screwdriver,’ Rayner asked, calmly.

‘Eff off.’

‘Come on, have some common sense. You wouldn’t want to do six months for carrying an offensive weapon. Not in Dunnabeg Youth Correction Institute, anyway. Truly, it’s a grim place. Most of the cells are without windows, the meals are awful, half an hour of telly a week, church on Sunday, no mobile phones, and bullying is out of control — those guys would punch a kid like you in the face without a second thought, steal your food, smash your radio, raid your stash.’

Rayner’s description had worried the lad. ‘Can you not hide from them?’

‘Well, you might be able to hide from them, because you can see them coming from a distance. They’re the ones wearing Y C I uniforms.’

The youth handed over the screwdriver, holding it courteously by the blade.

‘Thanks. I can see we’re going to get along fine,’ said Rayner. ‘I’m sure I recognise you from your mugshot. What’s your name?’

‘John Smith,’ growled the youth.

‘Are you sure it’s not Ewan Turner?’

‘Completely,’ said Ewan Turner, with a snarl that would have done credit to a hungry Rottweiler.

‘And you don’t live in Flat 15, Waldegrave House, Falgour?’

‘No,’ said Ewan Turner, who lived in Flat 15, Waldegrave House, Falgour, ‘I live over there.’

‘Which one?’ Rayner asked him. ‘What’s the door number?’

‘I don’t know. I can’t see it from here.’

‘Have you tried going to Specsavers?’ Rayner suggested.

‘No, it’s pointless, ’cause they take all the cash to the bank every night.’

‘Incidentally,’ Rayner continued, ‘while I think of asking, which school do you go to?’

‘I don’t go to school.’

‘Because someone might ask me which school you go to. When you did go to school, which one was it?’

‘Carpenter’s.’

‘Carpenter’s School in Falgour. I must’ve got you confused with someone else. I’m sorry. We all make mistakes. So how about I take you to that house over the way and you let yourself in with your key, and you’ll hear no more about it. Do you think I can trust you not to do anything silly like this again?’

‘I wasn’t doing anything silly at all. I was trying to get some fags.’

‘ ’Cause you can get into an awful lot of trouble if anyone sees you and thinks that you’re trying to break in.’

‘Hey, I just remembered,’ said Ewan, ‘I left my door key at my mate’s house in Falgour.’

Rayner looked up at the clock on the harbour tower. ‘If we rush, you’ll just make the train to Falgour.’

‘I would, but I haven’t got any money.’

‘Oh, you poor soul. And it’s a long walk, too. Is that why you were trying to break the lock on the newsagent’s door?’

‘No, I wanted a packet of fags.’

‘Without money?’ Rayner looked at her watch. ‘Giving them away free now, are they? Let’s get you onto the train. We’ve got five minutes. I don’t know how you’re going to get back home after you’ve picked your keys up, though. Do you think we should knock on the door of your house and see whether there’s anyone at home? Or we could break the lock with that screwdriver of yours. You could fetch your key from your mate’s house in the morning. Your Mum will surely lend you the train fare.’

‘I need to bloody go to Falgour.’

‘I’ll see what I can do.’ She looked at the harbour clock in the distance. ‘We can just get you on the train, I think, but we’ll have to rush.’

Theo came out from the shadows and caught up with Rayner and Ewan. ‘Six minutes, actually,’ he said.

‘You don’t mind if my friend comes with us, I hope?’ said Rayner to both of them, and neither objected.

|

|

|

Rosentyre station at night |

As they crossed the footbridge at the station, the last train of the day grumbled in. They were the only departures. The guard stood on the platform watching three late night travellers leave the train. Rayner beckoned him across.

‘A child’s single to Falgour, please.’

‘Don’t you need one for yourself as well?’

‘No, thank you. I’m going home. The ticket’s for my friend John here. He left his door keys and his money at his mate’s house and he needs to go back and get them.’

‘One pound fifty.’ Rayner paid for the ticket and the guard issued it, asking quietly, ‘Are you sure I won’t find him stumbling around first class, smoking dope, like he was a couple of days ago?’

‘Oh, I hope not.’ said Rayner. ‘It would upset me dreadfully if my John did anything like that. He’d be letting me down awfully.’

With a reply of, ‘I hope you’re right,’ the guard returned to the back cab and rang the bell. The engines revved and the train moved off.

‘Was that the last train?’ Rayner asked Theo.

‘Yes. No more trains either way until five thirty in the morning.’

‘I reckon we’ve both earned a rest.’ Rayner pushed open the door of the Ladies Only Waiting Room. It was a room with three benches covered with dull coloured vinyl, a fireplace that hadn’t been lit for years, grubby windows, unwashed peach coloured curtains along one wall and a couple of lights hanging from the ceiling. ‘Nobody ever comes in here,’ she said as they walked in.

‘You mean, like we just did?’

Rayner took off her cap and laid it on one of the benches. ‘I’m not in uniform now,’ she said, as she turned the lights off. ‘I reckon we could spend a couple of hours in here.’

Rayner unwound her tie, took off her uniform jacket and shirt, and laid them beside the cap.

Entranced by her, Theo wrapped his arms around her and was tussling with her bra clip when a train pulled into the platform. It was about two thirds full. The guard came over and opened the waiting room door.

‘You’re lucky I saw you. Sorry we’re late. Last train for— Oh!’ he called, and he looked the other way as he continued quietly, ‘I am sorry. Switch everything off when you leave.’

With that, he closed the door quietly, returned to the back cab and sent the train on its way.

The phone on Horatio’s desk trilled. ‘Horatio,’ said Horatio.