Nine a. m., as promised, I showed up at the police station on Greyfield Square. A young lady, looking most enticing in her green ribbed sweater and beige patterned skirt said, ‘Morning, Mr Corsair. I'm Jane. Come with me and meet Mr Thomson.’

Nine a. m., as promised, I showed up at the police station on Greyfield Square. A young lady, looking most enticing in her green ribbed sweater and beige patterned skirt said, ‘Morning, Mr Corsair. I'm Jane. Come with me and meet Mr Thomson.’

She led me from the front desk into Ellis Thomson’s office. The man himself was sitting behind the desk.

She led me from the front desk into Ellis Thomson’s office. The man himself was sitting behind the desk.

‘This is Sam Corsair, sir,’ she told him, ‘the consulting detective.’

‘Sam Corsair P. I.,’

I said to them both. ‘Pleased to meet you at last.’

‘I’m very glad you’re here,’ came the reply. ‘I hope you’ve had a good trip.’

‘I did. Comfortable flight, great hotel. Thanks for fixing it all up for me.’

‘Don’t thank me. Jane fixed it all up.’

‘That’s me,’ said the lady. She gave me a smile like the sun coming out from the clouds.

‘Jane here’s my secretary. Whatever you need, ask Jane. She can fix anything.’

‘Anything?’ I asked her.

‘Anything,’ she breathed, ‘For instance, I booked the Sandringham Hotel for you. You’ll have no complaints. Ellis is right, though. I can arrange absolutely anything.’ She put the emphasis on that word anything.

‘Taxi driver said the same thing as I left the Union Station. Marvellous.’

‘Union Station?’ Jane sounded as though she had never heard of the place. ‘Where’s that?’

‘Halfway along Main Street,’ I told her. ‘Railroad station — you must have noticed it.’

‘I think he means Waverley,’ said Ellis.

Come to think of it, that was the name, more or less.

‘And in this envelope,’ she picked up a manila envelope from Ellis’s desk and held it out to me, ‘here’s your warrant card and the keys to your car.’

‘My car?’ I thought I'd left it up an alley off Carlsberg Avenue, New York.

‘The bright red Jaguar Mark One in the staff car park.’

‘The bright red Jaguar Mark One in the staff car park.’

‘I suppose it says, “Here come the cops, hide on the double!” in big letters on both sides.’

‘It’s unmarked, sir,’ Jane flashed another smile. ‘But it won’t go un-noticed.’

‘Jaguar Mark 1, best car that’s ever been made. That should leave an impression behind,’ I said.

I took the envelope. Jane turned on one shiny, black four-inch heel and clicked out of the office, with a look over her shoulder that said, ‘See you later.’ I watched after her. If her skirt had been any tighter, she would’ve fallen over.

I needed a few seconds to get my mind back onto the investigation.

‘Any progress with the case?’ I asked Ellis.

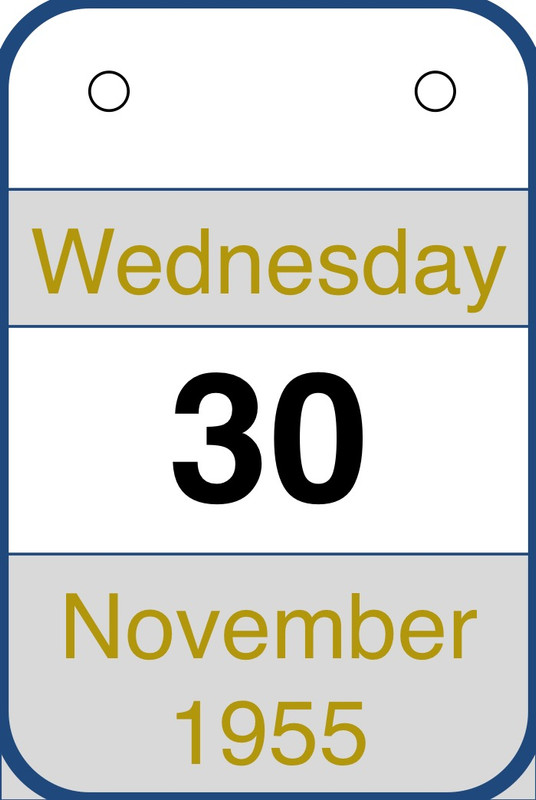

‘Things are not improving. There was another incident over the week-end.’

‘What happened? Was anyone hurt? Anyone been caught?’

‘No, nobody hurt, just a bit shaken. An attempted break-in that looks similar to the other break-ins.’

‘So it could be the guy we’re looking for.’

‘My own thoughts exactly. Corsair, I think the best thing would be for you to go and talk to the woman who appears to have been the intended victim. I don’t want to influence your findings and besides, it’d be best if you spoke to her before she forgets all about it. I’ll brief you when we have a bit of time on our hands.’

‘Sure, boss. Who and where?’

‘Her name’s Catríona Murray. She’s in the Grand Azure Hotel. Remember to drive on the left.’

The car was beautiful, but I got in, and at first I couldn’t find the steering wheel. Then I realised, of course, that I had to get into the car on the driver’s side. The right hand side. Even after that, I found it awkward to drive off, because the gear-change was on the wrong side. Who would want a left handed gear-change? Was every driver in Scotland left handed? But I did remember to drive on the left. I got honked at a few times, ’cause a car like that makes you enemies.

Ms Murray was an actress currently making a movie. When not actually performing, she hung out in the Grand Azure Hotel, which rambled impressively across large, afforested grounds in the west of the city. The Jaguar covered the ground easily and got me hard stares from the sidewalks. I showed the receptionist my warrant card and said the magic word. ‘Police. I’m looking for Catríona Murray.’

‘Is she in trouble?’ the receptionist asked.

‘No, just routine stuff,’ I said. ‘Which room’s she in?’

The receptionist told me that Ms Murray was on the VIP floor, Suite 516.

Every P. I. knows that a door is a dangerous thing. You never know who, or what, is on the other side of it.

I couldn’t draw my gun before banging on the door, because I didn’t have one. British police notoriously don’t carry guns. I couldn’t hammer on the door with my baton either, because I didn’t have a baton. Jeez, with no gun and no baton, how do these guys ever arrest anybody? In desperation, I took one shoe off, hammered on the door with the heel and bellowed, ‘L. B. P. D.!

Police! — Open up!’

The door opened. The charming face and blonde hair that I recognised from a thousand margarine commercials looked straight at me and spoke pure California. Her hair was a bird’s nest, her dress was crumpled, her eye make-up was running down her cheeks and the mingled aromas of costly perfume and superior cognac flooded over me. ‘You’re new to Scotland, aren’t you, Officer?’

The door opened. The charming face and blonde hair that I recognised from a thousand margarine commercials looked straight at me and spoke pure California. Her hair was a bird’s nest, her dress was crumpled, her eye make-up was running down her cheeks and the mingled aromas of costly perfume and superior cognac flooded over me. ‘You’re new to Scotland, aren’t you, Officer?’

‘It’s my first day on the job,’ I said.

‘You’ll go far. Come in.’

‘I will,’ I said, ‘once I’ve put this shoe back on.’

Miss Murray was wearing a bright red dress that flashed and sparkled in the light.

‘You must excuse me,’ she said, ‘but I was at a party late last night and I was so tired afterwards that I slept in my clothes.’

‘You look fine to me.’

‘Are you here about the intruder?’

‘Yeah, I sure am. Do you want to tell me about him?’

‘Well, this morning when she came to tidy my room, the cleaner told me that yesterday morning, while she was cleaning in here, a man, handsome and very well dressed, walked into the room. ’Course she yelled at him to get out, and he did. But he didn’t look like a burglar. He fitted in with these plush surroundings.’

‘What did he look like? Tall, short, young, old, beard, glasses?’

‘I don’t know, Officer. The cleaner saw him. I didn’t.’

‘Is that all you know?’

‘Yes. Except for one strange thing.’

‘Which was?’

‘He was carrying a box of chocolates.’ Ms Murray’s expression was of pure incomprehension.

‘You’re kidding me.’

‘No. Straight up. The cleaner said he had a big, purple box of Chertsey chocolates.’

‘An American brand. Maybe he thinks you’re malnourished.’

‘Or homesick, maybe.’

‘I’ll need to speak to the cleaner, if I can find her. Did you get her name, by any chance?’

‘Uh-uh,’ meaning, ‘no.’

‘Can you describe her, then?’

‘Fifty years old, overweight, lots of rings—’

There was a gentle tap at the door.

‘Duty manager,’ said a man’s voice from the corridor. ‘Are you all right, Ms Murray?’

‘Perfectly,’ she said, loudly, without opening the door. ‘Nothing to worry about.’

‘I understand there was a bit of a kerfuffle here.’

‘Someone needed to talk with me.’

‘Tell him to stick to “ ’Ello, ’ello” in future.’

I thanked Ms Murray, I said goodbye to her and I hurried into the corridor, where the Duty Manager stopped me. Brylcreemed hair, charcoal suit, club tie, starched white shirt: could’ve been a tailor’s dummy.

‘Where are you going?’ he demanded.

‘Sam Corsair,’ I introduced myself, ‘L. B. P. D. Can you tell me who cleaned this room yesterday? I need to talk to her.’

‘I don’t know her name. An agency sends the cleaners.’

‘Great! Can you tell me which agency it is? I’ll need to rattle their cage.’

‘Spring Cleaning. I have their phone number somewhere.’ He fumbled for his wallet and gave me their business card.

‘Who’s your contact there?’

‘The owner. Joshua Spring,’ said the duty manager.

Things were looking up — I had my first eye-witness.

I woke up in the Sandringham at about seven in the morning. I’d slept well without the street-cars of Carlsberg Avenue rattling me awake every thirty minutes.

I woke up in the Sandringham at about seven in the morning. I’d slept well without the street-cars of Carlsberg Avenue rattling me awake every thirty minutes.

The restaurant served Scottish breakfast. I could see what that involved because, all around me, other customers were eating from the same menu. How did people eat all that? I never saw so much food on the same plate. I was surprised that it all fitted. Eating all that — if I could eat all that — was going to take a while, so I took the pencil out of my shirt pocket, picked up the paper napkin off the table, and told my pencil that I was fresh out of Basildon Bond but the napkin was perfectly good stationery. Then the waitress, early twenties, false eyelashes, cute face, said ‘Good morning, Mr Corsair,’ and brought me an orange juice, a dish of oatmeal, a jar of honey and a teaspoon. I spooned honey into the oatmeal and I tried to get my thoughts into order.

One, I wrote, and underlined it.

Someone had gone into Catríona Murray’s room at the Grand Azure hotel.

I took a spoonful of oatmeal. Two.

The cleaner was working in Ms Murray’s room at the time. She (or was it he? Probably not) had asked the intruder to leave. He left. He didn’t argue or make any trouble.

Three.

The intruder was well dressed and he was carrying a box of chocolates.

Four.

The cleaner had been sent by an agency called Spring Cleaning.

I had finished the oatmeal and drunk the orange juice. The waitress brought me bacon, eggs, a sausage and a whole fry-up. Did they have maple syrup that I could pour over it, I asked. No, she said, they were clean out of it, but they’d get some for me by tomorrow. Did they have some coffee? Yes. Viennese, with cream and two sugars? She fetched it. It tasted every bit as good as the coffee from Fat Bruno’s shack in Statue Park, who could brew coffee for the Olympics.

I stabbed a round grey thing with my fork, cut it in two and ate half of it. Not bad, even though I had no idea what it was.

I carried on writing my list.

Five.

Spring Cleaning have an office at 60 Moray Circus. The boss of Spring Cleaning was called Joshua Spring. I had his business card in my wallet.

A thought struck me. I went back to point three and I added, ‘Not just any chocolates. Chertsey chocolates.’ Not a brand you’d buy to impress a lady, but an ordinary, work-a-day brand. The sort you buy to keep the kids quiet while you call your mistress. You never know, it might turn out to be important.

I sat still for a couple of minutes but I didn’t think of anything else. So far, so good. Touch wood, I had an eye-witness.

The waitress took my empty coffee cup, replaced it with a fresh, full one, and asked, ‘What do you think of haggis?’

‘Was that the round, grey slice of stuff?’

‘Yes, sir.’

Truth to tell, I couldn’t remember what it tasted like, so I said, ‘Absolutely delicious. Worth coming all the way from New York just to try it. Can you ask the Chef to wrap one up for me? Small enough to fit in the glove compartment. I can eat it for lunch.’

‘I’ll see what I can do,’ she said.

With the slice in the dash, I started the car and headed to Moray Circus a couple of miles away. It was a short, curved street, specially designed so that there was nowhere you could park by the kerb and not be run into by a speeding fire engine, or a ten ton truck being driven like one. Number 60 was a dusty wooden door with a fan-light and a brass handle that worked the doorbell. I’d found the right place. There was a very respectable black metal plate on the door with gold coloured writing etched on it. Spring Cleaning. First floor. Ring bell and wait, so I rang, I heard a bell ring somewhere on a floor above me, and I waited.

With the slice in the dash, I started the car and headed to Moray Circus a couple of miles away. It was a short, curved street, specially designed so that there was nowhere you could park by the kerb and not be run into by a speeding fire engine, or a ten ton truck being driven like one. Number 60 was a dusty wooden door with a fan-light and a brass handle that worked the doorbell. I’d found the right place. There was a very respectable black metal plate on the door with gold coloured writing etched on it. Spring Cleaning. First floor. Ring bell and wait, so I rang, I heard a bell ring somewhere on a floor above me, and I waited.

I heard distant footsteps, and with much creaking, the door opened. Behind it was a windowless box of a room maybe ten feet square, painted blue below the waist and cream above, and lit by one bare electric light bulb and what sunshine made it through the fanlight. It smelled of damp and dust. The man who opened the door was Mid East in appearance, bald, in a maroon cardigan, open neck shirt and grey pants. ‘This way,’ he said. There was only one way, a flight of stone steps going up. There was a letter-box on the back of the door. The man took a couple of letters out of the box and carried them with him. They were brown ones with windows. It seemed he had the same business problems that I did.

At the top of the stairs there were a couple of unmarked doors, and we went through the one on the left. It led into an office with enough room for a desk and a filing cabinet. On the desk, there were a phone and a tray for letters.

‘Good morning. Are you Joshua Spring?’ I asked.

‘Yes, sir. Trading as Spring Cleaning, employment agency.’

‘Sam Corsair, P. I., Lothian and Borders Police Department.’

‘I am most pleased to meet you,’ Mr Spring beamed. ‘In what may I assist you?’

‘Do you send a cleaner to the Grand Azure Hotel?’

‘Why, yes indeed.’

‘It’s very important I speak with her. I think she witnessed a crime being committed. Or maybe being attempted.’

‘Oh, dear. I hope she is not in trouble.’

‘Not at all. She ain’t got nothing to worry about. I just need to talk to her, that’s all.’

Mr Springer rifled through a box of index cards, found one and read it to me.

‘Her name is Soraya. Soraya Figueroa.’

‘How long’s she worked for you?’

‘Her first engagement was the tenth of August 1953. She has worked in the Grand Azure many weeks since then.’

‘You got her address?’

‘I have only her telephone number,’ he said.

‘Telephone number? How does a cleaner pay the bill for a telephone?’

‘That, I cannot say.’

Mr Spring wrote the number on a piece of scrap paper and gave it to me. I folded it and stored it in my wallet.

‘Thank you,’ I said, ‘Thanks for helping.’

‘Oh, it was nothing, I assure you.’

It was far from nothing. All I needed to do was talk to Soraya Figueroa, and I’d be away to a flying start.

Three p. m. I’d driven back to Greyfield Square. Just opposite the Police station, there was a terrace of half a dozen shops. Oak Terrace. I’d noticed a café shop that smelled okay.

They didn’t know what Viennese coffee was so I took a large paper cup of whatever was strongest, put a lid onto it and walked across. Jane said hi and told me that Ellis was in his office.

I knocked. Ellis was anxious to know what progress I’d made. I asked if there’d been any more break-ins. No, there were none. So I told him I had the phone number of an eye-witness.

‘Have you rung it yet?’

‘No, I haven’t. This is the first time I’ve been near a phone.’

‘Use mine,’ said Ellis, waving his arm towards the phone on the desk. ‘Go ahead, try it, don’t hang about,’ he told me.

I dialled the number. I didn’t hear it ring. I heard a strange noise, so I tried again. Again I heard the strange noise.

I held out the receiver to Ellis. ‘What’s this noise?’ I asked him.

Ellis took a listen and said, ‘That’s an unobtainable tone, Sam. It means there’s no such number.’

‘What do you mean, there ain’t no such number?’

‘It means the phone number doesn’t exist, or it doesn’t work, or the subscriber hasn’t paid the bill. Try talking to the operator.’

I called the operator.

‘She says the number doesn’t exist.’

‘Then you won’t be able to ring it,’ said Ellis. I’d worked that out for myself. ‘Not much you can do, unless whoever gave you the number wasn’t wearing glasses.’

‘Well, no, he wasn’t,’ I recalled.

‘Then he probably mis-read the number from his files. Go back and ask him to double check.’

That made sense. But we New Yorkers have a saying. Never do today what you can put off until tomorrow. I decided this could wait until tomorrow.

I went and sat in the office that Ellis had found for me. I drank the coffee and I ate the slice of haggis. Strange stuff, I thought. Then Jane came in without knocking and asked quietly, whether I had five minutes. I said sure, I had five minutes, but after six minutes I was going back to the Sandringham.

Jane said, ‘I don’t know much about men’s tastes, Mr Corsair. Could you advise me?’

‘Sure. What’s the problem?’

Leaning forward farther than necessary, Jane released an evocative cloud of perfume and showed me a lingerie catalogue. She turned to a page with three styles of nightwear on it, all of them seductive, and she asked me which one I liked best. Any of them would have attracted me, I thought, but I said, the red one.

‘This one here?’ she asked, pointing at the red one.

‘Yes, that’s definitely the one for me.’

‘Do you think I’d look good in that?’

‘Stunning,’ I said, ‘irresistible.’

‘Sam,’ she said, picking up the catalogue, ‘I have a favour to ask you.’

‘Ask away, lady.’

‘I have a hot date tonight at the Sandringham,’ she told me. ‘Could you give me a lift over there?’

‘He’s a lucky man,’ I said. ‘Who is he?’

‘Blind date,’ she said. ‘And, anyway, I always wanted to ride in a Jaguar.’

Jane went to fetch her bag, then I gave her a ride to the Sandringham and I left her to meet her new friend in the hotel bar.

I took to my bed around eleven. I’d just made myself comfortable when there was a quiet tap on the door.

I took to my bed around eleven. I’d just made myself comfortable when there was a quiet tap on the door.

A lady’s voice called, ‘Room service.’

‘I didn’t order room service.’

‘One Viennese coffee and someone to share it with.’

I was intrigued. ‘Who is it?’

‘Only me,’ said the voice.

I opened the door, and there was Jane, from the office, wearing a short red dress wrapped tightly around the curves of her body and carrying a china cup of coffee.

‘Sam!’ Jane put one arm around me and pulled me into a kiss. Somehow she managed it without spilling the coffee. ‘This is for you. Are you going to invite me in?’

I was transfixed. ‘Sure thing, doll. Come in.’ I took the coffee, put it on the table and shut the door behind her. ‘What happened to your hot date?’

‘He never showed up.’

‘You’ve been drinking alone?’

‘Two glasses of wine. Help me take the dress off.’

‘You sure about this?’

‘I never wanted anyone more. Don’t rush.’

We lay down together and twined our arms around each other. ‘See?’ she said, ‘I said I could fix anything.’

After a wonderful night, we woke together.

After a wonderful night, we woke together.

I dropped Jane off at Greyfield Square.

She smiled and told me to have dinner at half past seven in the hotel.

Then I threaded through the architecture of the New Town back to 60 Moray Circus.

Where else is there a New Town that was built in the eighteenth century? They ought to call it something else, like the Old Town. Or the Extremely Old Town. That would do.

I walked up to the blue front door.

The sign on the door had changed.

It no longer said, ‘Spring Cleaning.’ Now it read, ‘Happy Land Tarot Readings and Palmistry. First Floor.’ Followed by the inevitable ‘Ring Bell and Wait.’

I banged my knuckles on the door. ‘L. B. P. D! Open up.’ I knocked so hard that the sign fell off the door onto the step, and it landed face down. On the back was the sign that I’d seen here yesterday: ‘Spring Cleaning.’ It looked as though somebody had left in a hurry and really didn’t want to see me again.

I picked the sign up, avoiding the glue that had been sticking it onto the door.

A slender Black woman in a flamboyant, brilliantly coloured Carnival outfit opened the door. If you’d caught sight of that outfit out of the corner of your eye, you’d have thought the room had caught fire.

A slender Black woman in a flamboyant, brilliantly coloured Carnival outfit opened the door. If you’d caught sight of that outfit out of the corner of your eye, you’d have thought the room had caught fire.

‘Morning, Officer.’ Trinidad accent. I would have known it anywhere.

‘I’m Sam Corsair, P. I.,’ I said. ‘I’m looking for Joshua Spring. You ever heard of him? Do you know where he is?’

‘Chahrazad Sihème’ She introduced herself. ‘I never heard of him. Do you want to come up to my office?’

We climbed the stairs. Not only was the office in the same place as it was yesterday, but it was equipped with the same furniture as yesterday, apart from a crystal ball and two decks of cards on the coffee table.

‘He was here yesterday,’ I said, ‘sitting in that chair. A lot uglier than you but he knows something that I want to find out about.’

‘I was in this chair from nine to five yesterday with an hour for lunch and two fifteen-minute tea breaks, doing tarots and divining the future.’

‘Mind if I take a look around your office?’

‘If you think Joshua Spring might be hiding in the filing cabinet, sure, be my guest, but don’t upset the Spirit World,’ she told me. ‘They scare easily and they can be pretty vindictive.’

I thought, in that outfit, she would scare the entire spirit world to Kingdom Come, but I kept it to myself. ‘How do you spell that name?’ I asked instead.

She laughed.

‘How long have you worked in this office?’ I asked.

‘I moved in…’ She paused for thought. ‘July 1953.’

‘Almost two and a half years,’ I worked out. ‘Are you sure about that?’

‘Sure I’m sure. But if you want the exact date, you can ask

House to House Removals.

They moved me in here.’

‘I might just do that.’

‘Want me to ask the Spirit World where Joshua Spring got to?’ Chahrazad asked me.

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘They can’t know less than I do. How much is this celestial divination going to cost the Police Department?’

Chahrazad plucked a figure from the air. ‘How about five shillings?’

I paid the lady, who must have divined the exact amount of cash I had on me and then asked for it. Two heavy silver coins. British money weighs a ton. No wonder the British invented cheques. Where do the Brits get enough strength to carry enough money for a day's cups of tea, bus fares and tinned food? She gave the deck of cards to me and told me to shuffle it. I did. Then she took the cards back, flourished one hand over them and dealt herself four cards. She made a show of turning the cards face up.

‘Nothing to worry about,’ she said, ‘there’s the Justice card. You’re going to get your man.’

‘Anything else I need to know?’

‘The Tower card. You’ll be stronger afterwards.’

‘Any richer?’

‘Not that I can see here. Sorry!’

‘Do the Spirits say anything about boxes of chocolates?’

‘Not that I can see,’ said Chahrazad. ‘Should they?’

‘You never know,’ I said, ‘there could have been.’

Without a search warrant and a team of cops to do the hard graft and sort out the fights, I wasn’t going to find out any more. I thanked Miss Sihème and left. I was sure going to miss her coat of many colours.

On the way out I looked at the other doors on the same stair, and I even spoke to the occupants when there were any. Nobody had heard of Joshua Spring. Nobody had even heard anything go bump in the night.

I motored back to Greyfield Square and, suddenly remembering what the coffee was like in the Police canteen, I parked on Oak Terrace and went into the café there. The cutie behind the counter smiled at me.

‘What can I get you?’

‘Your strongest coffee, in a paper cup with a lid.’

‘Black or white?’

‘I’ll sit in whichever section has the most room.’

For a moment, the lady seemed nonplussed. ‘I mean, do you want milk in your coffee?’

‘Oh. Now I understand. Give me coffee with milk.’

‘Sure. Ninepence.’

I reached into my pocket and I found it empty. I realised that the few British coins I had were somewhere in my room in the Sandringham. No panic. I still had a couple of dollar bills in my wallet. I held a dollar bill out to her.

‘Keep the change,’ I said.

‘I’m sorry,’ said the lady, who looked as though she had asked for bread and been offered a stone. ‘That’s American money.’

‘Sure,’ I said, open mouthed with astonishment, ‘that’s the finest money in the world.’

I hadn’t noticed Ellis Thomson, out of uniform, sitting at a table at the farther end of the café. ‘Here, Officer Corsair,’ he called, ‘you can have this one on me.’

‘I’m much obliged,’ I said, taking the millstone-size copper coins that he was holding up, ‘but what’s she got against dollars?’

‘Nothing,’ he said, ‘except this is Scotland. I thought you might come in here for coffee — can’t say I blame you. We can talk here. It’s warmer than the Police station and the coffee’s better.’

‘Suits me,’ I said.

‘How have you been getting on?’ Ellis asked.

‘Talked to the victim. The woman who cleaned the hotel room saw the intruder and chased him out of the building. So I thought I’d got a witness. I went to the agency that sent the cleaner and they gave me a false phone number. Today the agency’s office has changed into a different business altogether. No trace of the owner I saw yesterday. So I haven’t traced the witness.’

‘Well, it’s early days yet. I hope things improve as we go along.’

‘They’ll get better, if only because they couldn’t get any worse,’ I observed.

The Victims

|

|

|

|

|

Tiffany

Walters |

Lauralee

Yates |

Trudy

Humphreys |

Catríona

Murray |

|

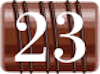

‘So,’ Ellis said, ‘I’ve got the files on these break-ins here.’ He produced a quarto manila folder. ‘The story so far. That’s all the background information I have.’

‘Good, because I have a lot more questions than answers. How many of these break-ins have there been?’

‘Three that the Police know about, before Catríona Murray. All names that you’ve probably heard.

The first victim was Tiffany Walters, the culprit—’

‘Tiffany Walters as in, the actress?’

‘The same.’

‘She’s been in

Pure.

‘She’s been in

Pure.

‘Has she? I wouldn’t know. I don’t buy magazines like Pure.’

‘You mean there are other magazines like Pure? Anyway, Miss Walters was centrefold in the October issue. …Well, so I am told.’

Ellis cleared his throat and went on reading from his folder. ‘On 19 April ’54, someone appears to have skied down a long slope, Aviemore way, and broken into the chalet at the bottom, where Miss Walters was a guest. The man missed an avalanche a few seconds later by the skin of his teeth.’

‘What did he take?’

‘Nothing at all.’ He seemed to be waiting for my incredulous reaction, and I produced one.

‘What do you mean?’ I asked. ‘What sort of burglar doesn’t steal anything?’

‘Only a completely incompetent one. Nothing seems to have gone missing after any of these break-ins. Yet the culprit shows remarkable skill in finding out where his target is staying and he uses the most outlandish means to get there.’

‘Ski-ing downhill to a chalet … May I see that photograph? Thanks … to a chalet which has a perfectly good road past its front door.’

‘Ski-ing downhill to a chalet … May I see that photograph? Thanks … to a chalet which has a perfectly good road past its front door.’

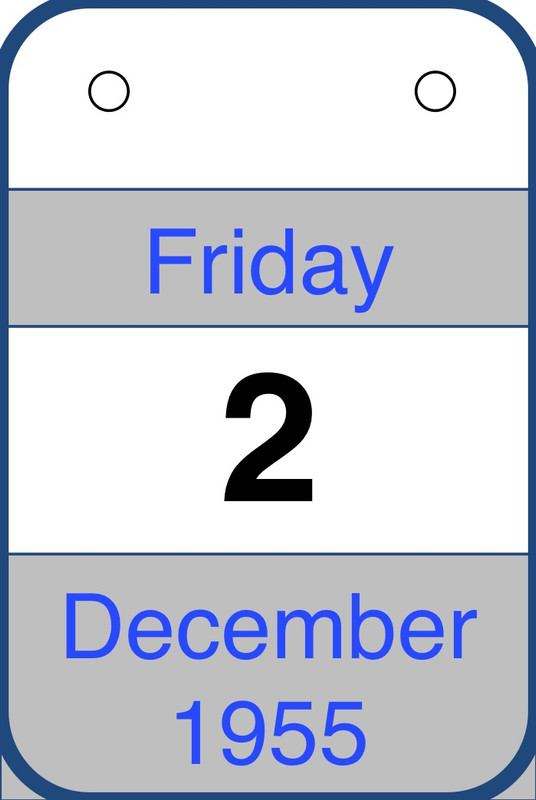

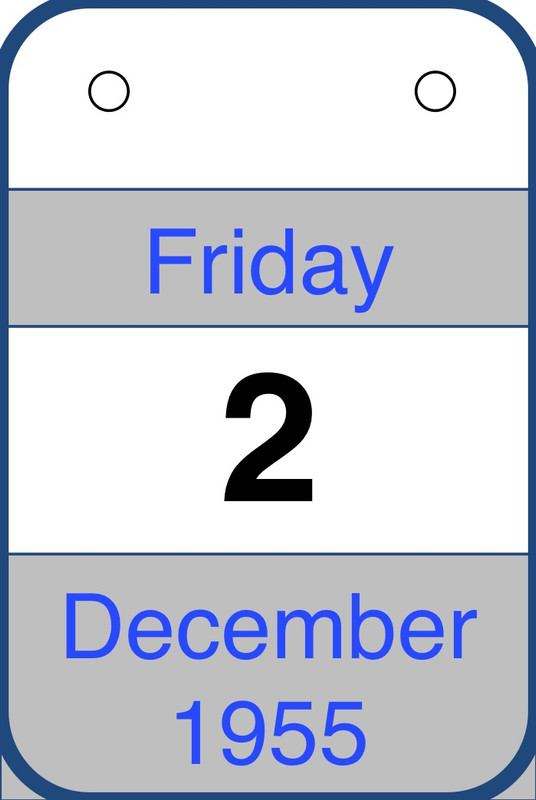

‘In the second break-in, Lauralee Yates—’

‘Another famous name.’

‘She’s in films. On 2 May 1955 this guy set off an explosion in the reconstructed fort, somewhere in the Pentlands, where the victim was working. Making a film about El Alamein. Overcame an armed security guard, despite apparently being unarmed himself.’

‘Was the guard hurt? Still above ground and breathing without assistance?’

‘The guard was in hospital overnight. When he came round, I spoke to him, but he didn’t seem to remember anything useful.’

‘Our man knows his unarmed combat, then.’

‘Absolutely. The third victim was Trudy Humphreys, stage actress, presently working in the Bevan Theatre in Glasgow.

Now listen to this: On 2 November this year, she was a passenger on a small boat,

M. V. Cluaran an Luchd-siubhail,

registered in Portree and licensed to carry four crew and eight fare-paying passengers on pleasure trips close to shore.

Now listen to this: On 2 November this year, she was a passenger on a small boat,

M. V. Cluaran an Luchd-siubhail,

registered in Portree and licensed to carry four crew and eight fare-paying passengers on pleasure trips close to shore.

‘Do we know anything else about it? Who owns it? Who was the skipper? Who were the other passengers?’

‘Anything like that will be with the harbour-master or the owner. So we know only that Miss Humphreys was taking a pleasure trip which involved a night at anchor somewhere off Neist Point. In the middle of the night, our man appears to have dived 140 feet from the cliff into deep water and struck out to the boat. Boot-prints on the boat matched the ones on the cliff-top. Size Ten Hurberts. Talk about going equipped.’

‘Good Lord. So he’s some tough guy. It’s a miracle he’s still alive, even so.’

‘Alive, so far as anyone knows. And then there was the break-in into Catríona Murray’s room in the Grand Azure, last Saturday, the twenty-sixth. You know all about that.’

‘I wish I did. I’m still working on that one.’

‘But you haven’t heard the whole story. Here’s the strange part. None of the victims caught a glimpse of him.

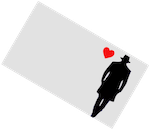

And he left his calling card and a box of chocolates where the lady would find it when she returned. Or in Miss Humphreys’s case, when she woke up.’

And he left his calling card and a box of chocolates where the lady would find it when she returned. Or in Miss Humphreys’s case, when she woke up.’

‘But by then—’

‘Exactly,’ said Ellis, ‘he was miles away.’

‘So he can turn his hand to stake-outs as well. What did the calling card tell you?’

‘Nothing. Blank with a printed silhouette and a heart.’

‘And there’s something else a bit odd. Chocolate was rationed until the fourth of July last year—’

‘A good choice of date,’ I said. ‘Children must have been running around eating their first liquorice allsort in five years and singing the National Anthem to celebrate Independence Day.’

‘I’m afraid Scotland hasn’t had its Independence Day yet.’

‘Pity, ’cause that’s a great day. How many sweets did they let you have?’

‘Two or three ounces a week. And you know the brand names. Carberry, Fyre, Marr, McInshott, Squaretree. Now, our miracle man leaves Chertsey chocolates for his victims. Chertsey. None of us has heard of it.’

‘Chertsey? That’s a leading brand in the U. S. Can I see one of the boxes that he left?’

‘There are a couple of empty boxes in the evidence store, and the business cards that were left with them. But of course…’

‘I’m ahead of you. Chocolate was still on the ration when the first two break-ins occurred. This guy risks his neck to give a lady a one-pound box of American chocolates. A month’s ration, in a good month. So, naturally, the ladies ate the chocolates, probably shared them with other people, so the chocolates wouldn’t have survived for long. All that evidence, eaten before anybody thought of telling the Police they’d been broken into.’

I picked up the manila folder and leafed through it. Photos, statements, couple of maps. Good for confirming everything you already knew about the case, but I didn’t.

‘Take it,’ Ellis said. ‘I’ll tell Jane that you’ve got it.’

‘Thanks. I need to go through all this,’ I said, ‘and then I need to think. But I can tell you one thing already.’

Ellis suddenly looked interested.‘Please do.’

‘There’s only one type of man who could have done all that. He’s a U. S. Marine.’

‘Very probably,’ said Ellis. ‘Very probably indeed.’

Ellis bought another paper cup of coffee and left the café. I watched him cross the road and disappear into the Police station. I noticed that he stood on the kerb and looked right first, then left, before he crossed. So I learned the secret. That was the reason the drivers hadn’t honked their horns, slammed the brakes on or run him over as he stepped off the kerb.

‘Behind these break-ins there’s a U. S. Marine,’ I said to myself as I finished the coffee, ‘or I’ll eat my hat.’

Jane had told me that seven thirty was a good time to have dinner. At seven thirty, I was alone in the restaurant at the Sandringham, going over what I knew and trying to get the measure of it all.

Jane had told me that seven thirty was a good time to have dinner. At seven thirty, I was alone in the restaurant at the Sandringham, going over what I knew and trying to get the measure of it all.

The first thought that occurred to me was, maybe, this guy just enjoyed pestering ladies. These were all ladies that anyone who read the papers would’ve heard about. Or anyone who read Pure, or other magazines that shared the same model agencies. But the ladies never saw him. I guessed it was a

he,

although maybe it was a woman, driven to house-breaking by lust or envy.

He could have pestered them much more easily if he just banged on their doors, stared in their windows, wrote them letters, sent them bunches of roses, called them or stood outside the front window playing My love is like a red, red rose on the bagpipe. Instead he went to extraordinary lengths to reach them by the most strenuous and dangerous means imaginable, and then he kept out of sight.

A waitress in a neat black dress, frilly linen cap and an apron, came over to me and said ‘Good evening. Which room are you staying in?’

‘Gwil-lee-mott,’ I said, phonetically.

‘I mean the name of the room.’

‘Gwil-le-mott,’ I said again, phonetically, but slower.

‘Are you in Guillemot?’ she asked.

I thought for an instant. ‘Yeah, I think I might be. Get me a chicken sandwich with fries, cover it with slaw and hold the mayo.’

She looked a little flustered for a second. Then she gave me a menu, a single sheet of mimeo’d paper, ‘Have a look through tonight’s menu, sir, and I’ll come back and take your order. Would you care for a drink?’

‘Get me a Bud straight out of the ice-box.’

That flustered look returned for a moment. ‘The wine list is on the back of the menu, sir.’

‘Oh, I see,’ I said, ‘thank you.’

I stared at the Wine list, and I called the waitress back. ‘Hey! Is one of these a beer?’

‘I’ll fetch you a pint of draught bitter,’ she said, ‘unless you’d prefer a bottle of brown ale.’

‘Draught bitter sounds perfect,’ I said, despite not knowing what it was. I noticed the word chicken on the menu, and I knew what that was. ‘Here,’ I said, pointing to it, ‘may I have one of those?’

‘Yes, sir.’ She smiled, probably relieved that I’d understood something at last, she wrote it down and disappeared.

Then there were the boxes of chocolates this guy was handing out. Chertsey wasn’t on sale in Britain, yet this guy had enough of it to give away while chocolate in England was still on the ration. Scotland, not really England at all — glad that I wasn’t speaking out loud. But Chertsey was mass-produced, assembly line confectionery. Not hand-made, exotic or expensive in the least. Worth less than a dollar. If you wanted to impress a lady, you wouldn’t give her Chertsey. You’d spend five times as much and you’d give her Butler or ten times as much and give her Soubré Reserve. And there was nothing unusual in the boxes, or there was and nobody had told me about it: no jewellery, no drugs, no money. Just a box of chocolates that the lady could’ve bought with spare change at any corner drugstore.

I took a swig of draught bitter. Strange stuff. It had a flavour. I never knew beer could have a flavour.

I heard Jane before I saw her. ‘Sam!’ She was coming in the door, behind me. ‘I hoped I’d find you here.’ She came into view, all tight dress, high heels, short skirt and man-eating perfume. I stood up and she put her arms around me. I kissed her for a while. You have to kiss women who look that way and dress that way, because if they didn’t want to be kissed, they wouldn’t have dressed that way. ‘Want to buy me dinner?’

‘I thought you’d never ask,’ I said. ‘Don’t sit opposite me. Sit on one side where I can hold hands with you.’

She sat on my left as closely as she could pull her chair, and she picked up the menu. Half a minute later, my waitress returned.

‘You have beef on the menu,’ Jane said. ‘Angus or Argentine?’

‘We have some Angus left,’ said the waitress.

‘I'll have Angus beef, then, and if it’s all right with you, Sam, a bottle of the red burgundy and two glasses.’

I said, ‘Sure thing.’

Jane looked straight across at me and smiled that sunshine smile. ‘Don’t worry about the bill, Sam. You can put everything on expenses.’

‘Do you think I’d get away with that? ’Cause I don’t.’

‘Almost certainly, Sam, because I check the expense claims.’

The waitress retreated from view again.

Jane looked at me steadily. ‘What’s on your mind, Sam?’

‘These break-ins. Nothing about them makes much sense. Guy almost gets killed giving a very ordinary box of chocolates to a woman who makes headlines if she sneezes or she sweeps the floor. Doesn’t take anything and doesn’t talk to the lady. Leaves her a bit rattled, I guess. And then there’s the disappearing employment agency.’

‘You have to leave your work at work,’ said Jane. ‘Let’s eat and just enjoy being together. We could have a lot of fun.’

‘I kind-of hoped we would.’

‘We will. A lot, big boy.’

We ate, we talked about anything but the case, and when we finished Jane asked if we could go for a joy-ride. ‘Let’s drive to The Puddles. I’ll point the way.’

We ate, we talked about anything but the case, and when we finished Jane asked if we could go for a joy-ride. ‘Let’s drive to The Puddles. I’ll point the way.’

‘What’s The Puddles?’

‘Nature reserve where nobody ever goes. There’s a place to park near the beach, and no street lights.’

At about two o’clock in the morning we woke up, still naked and still lying together on the back seat of the car, still parked in the middle of a ring of tall trees and bushes at The Puddles.

At about two o’clock in the morning we woke up, still naked and still lying together on the back seat of the car, still parked in the middle of a ring of tall trees and bushes at The Puddles.

‘How was I, Sam?’ Jane asked.

‘Perfect. The best ever, that cannot be improved upon. Tell me,’ I asked as I walked around to the driving seat in nothing but my underpants, ‘do you want to come back to the Sandringham with me?’

‘I’d been looking forward to it,’ she said.

‘Well, it’s two o’clock in the morning and there’s no traffic on the streets,’ I said as I felt in the darkness for my clothes on the floor of the car, ‘so how’s about I drive us back on the right hand side of the road? I feel more comfortable if the car’s the right way round.’

‘Great idea, Sam.’ I was so pleased that Jane and I agreed. ‘What this car really needs is a high-speed head-on collision causing deaths and serious injuries and all of it your fault.’

‘Fantastic. Let’s go.’

I turned the key in the ignition.

‘What?’ Jane shrieked, and then she paused for breath. ‘Stop! Stop!’ Sam, when I say “Great idea,” I mean the it’s the stupidest thing I ever heard.’

‘Why’s that stupid?’ I switched off the ignition and craned my neck right around, so I was looking straight at Jane. She was half naked still and I couldn’t have looked away even if I’d wanted to. ‘It ain’t stupid. There’s no traffic. At this time in the morning we won’t hit anything bigger than a milkman. Three hundred million Americans drive on the right every day and nothing bad happens to any of them. Except the ones who get killed in accidents, of course, but they ain’t driving the cars, they’re stepping out in front of them without looking.’

‘Sam, let me explain. In Scotland, when somebody says, “Great idea,” or “This pouring rain is just the right weather for a long walk in the hills,” or “Five pounds is a very reasonable price for a bundle of firewood,” they mean the exact opposite.’

‘How about when a woman says she loves you?’

‘That’s true. It’s your cue to say “I love you too,” or “Let’s go to bed,” or “Marry me.” ’

‘Are those the only options?’

Jane giggled. ‘I’m not sure, but… Yes, pretty much.’

‘Which one do you want to hear?’

‘It’s two in the morning or thereabouts. I want to hear you say, let’s go to bed.’

I turned the ignition key and I drove us safely back to the Sandringham, on the left hand side of the road the whole way. The roads were empty. We didn’t see another car.

I gave Jane a ride to the café opposite the Police station, drove around the block for ten minutes so that she and I wouldn’t be seen arriving together, and then drove back into the car park.

I gave Jane a ride to the café opposite the Police station, drove around the block for ten minutes so that she and I wouldn’t be seen arriving together, and then drove back into the car park.

As soon as I went inside, Jane called to me. ‘Morning, Mr Corsair! I got you a coffee!’ She handed me a paper cup of coffee and added quietly, ‘Remember, half past seven tonight is dinner time.’

As soon as I went inside, Jane called to me. ‘Morning, Mr Corsair! I got you a coffee!’ She handed me a paper cup of coffee and added quietly, ‘Remember, half past seven tonight is dinner time.’

‘I’ll be there, Jane,’ I said, ‘and I hope you will too. By the way, your perfume drives me wild.’

‘It’s Infatuation.’

‘It works on me.’

‘Are you infatuated with me?’

‘Completely and totally,’ I said, and Jane smiled.

Of all the things I’d seen and heard since I touched down in Scotland, the one that most troubled me was the overnight disappearance of

Spring Cleaning, Joshua Spring’s employment agency, and its sudden replacement by Happy Land and its — as far as I knew — sole member of staff, Chahrazad Sihème. Maybe Spring or Sihème had form.

Jane would know where to start. I picked up my reporter’s notebook and a pencil, and I went back to her desk by the public entrance. ‘Jane, have you got five minutes?’

‘I have all the time you want, Officer Corsair.’

‘Where’s the archive?’

‘Criminal records? Everything’s in the records room. I’ll show you where it is.’

The records room was a windowless, airless walk-in cupboard at the back of the station that stank of hot sweaty policemen needing to find pieces of ancient paper in an emergency. Jane pushed the plain wooden door open, showed me in and closed it again. Inside, she put her arms around me and gave me a passionate kiss.

‘It’s all in these filing cabinets?’

‘Aye. Thirty thousand records, alphabetically by surname. All you have to know is how to spell your suspect’s name. Good luck.’

Jane kissed me again and left. Maybe I really did mean something to her.

Less than an hour later, I’d found something.

SPRING, Joshua

32/4 Pearl Chare, Edinburgh 1

20 October 1942, Licensing (Scotland) Act, Found Guilty, Fine 4 guineas,

whatever they are.

20 April 1943, Licensing (Scotland) Act, Found Guilty, Fine 10 guineas.

Not much, but enough to see that someone called Joshua Spring lived on Pearl Chare, whatever that was, and had been dealing illegally in liquor. There was a newspaper cutting, with a handwritten note at the top, stapled to the card. Easier than writing up, I guess. The cutting was so dry and thin that I was worried in case it fell to pieces before I could read it all the way through.

The Scotsman 22/10/42 p. 5

48 BOTTLES OF UNTAXED WHISKY AND BEER

Last Tuesday, 20 October, one of the directors of J. S. Trading Ltd., Mr Joshua Spring, 22, of Pearl Chare in Edinburgh, pleaded guilty before the Sheriff Court to illegal trading in alcoholic beverages.

Constable Thomson, of the Lothian and Borders Police, stood in the witness box and testified before the Court that he had found twenty bottles of home made whisky, twenty eight bottles of beer and four of poitín in the basement of Mr Spring’s home. The drink was of uncertain quality and was to have been sold free of duty on the black market.…

Sheriff MacDougall ordered Spring to pay a fine of four guineas.

Constable Thomson could only be Detective Sergeant Ellis Thomson with thirteen more years’ service, so I had found a high ranking officer who could — probably — tell me a bit more about Joshua Spring. Maybe he’s heard of JS Trading Inc. Maybe he even knew what a

guinea

is.

Ellis told me that he remembered, if vaguely, charging Joshua Spring with unlicensed trading in alcohol early on in the War, and as far as he knew Mr Spring had committed a very similar offence a couple of years later, but a junior officer dealt with that. Since the end of the war, though, Mr Spring’s life had been unblemished, at least if you believed the Sheriff Court.

He went on to tell me that a guinea was worth one pound and one shilling. It was a high class currency used for the prices of furniture and race-horses.

As for J. S. Trading Ltd., Ellis didn’t remember the company featuring in the case, and suggested that I try asking about it at Scottish Companies House. ‘They’ll tell you everything you don’t need to know,’ he said reassuringly, ‘and a lot more, if you don’t shut them up.’

As for J. S. Trading Ltd., Ellis didn’t remember the company featuring in the case, and suggested that I try asking about it at Scottish Companies House. ‘They’ll tell you everything you don’t need to know,’ he said reassuringly, ‘and a lot more, if you don’t shut them up.’

‘Sounds just the sort of place I’m looking for,’ I said. ‘Where is it?’

‘I think it’s in Sole Cross,’ he said. ‘Jane knows the place. She’ll go with you.’

One very pleasant ride in the Jaguar later, Scottish Companies House did, indeed, tell us everything there was to know, and a lot more as well, about J. S. Trading Ltd. Their office was in Stranraer, a hundred miles from Edinburgh and a two-horse town, fishing and ferries. Joshua Spring had become a director of the company while living in Edinburgh in 1939, when all the other directors had begun work there in 1928, when the company was founded. Jane noticed another oddity. The company banked at Martin’s, while alone among the directors Mr Spring had declared his own checking account at Victory Holdings.

Knowing all this, we introduced ourselves to the Sherlock with the

Sumlock.

‘I do not know anything about this company that isn’t in its accounts, Mr Corsair,’ said the forensic accountant, John Rowe, ‘but it’s this sort of irregularity that keeps me in a job, so stay in touch — I need you. It looks to me like a forgery. Shall I tell you how it works?’

‘As long as the explanation is shorter than

War and Peace,’ I said.

‘I think it would be very useful to know how he did it,’ Jane smiled. How did anyone do a smile as devastating as that?

‘Mr Spring chooses a small company whose name, or something about it, appeals to him. In this case the company is called J. S., which happen to be his initials, but are also the initials of the managing director and principal shareholder, one Jowan Stainton.

Having picked a company, Mr Spring comes in here and picks up a form called

Notification of the Appointment of Director,

fills it in with his own name and address and the name and number of his chosen company—’

‘Ain’t no phone number on here,’ I said.

‘Not a phone number, Mr Corsair, but a company number, which appears on more or less anything that the company publishes. Then Mr Spring forges the signature of its managing director, who knows nothing about it.’

‘Then he gives the form to you,’ I said, ‘and you don’t notice that the form ain’t kosher?’

‘Sometimes we do, but this one’s slipped through the net. Every month we get hundreds of the things, and understandably we sometimes get a little bit slipshod. There isn’t time to scrutinise every signature and telephone every company head office to double check.’

‘So,’ I said, ‘what happens if nobody notices the fakery?’

‘Well, when the notification etc. is believed and accepted, we send a confirmation to Mr Spring and another one to the company, which telephones us if they notice anything suspicious. Except they don’t, of course, because its most junior employee picks the confirmation letter up off the doormat, looks at it, sees that it’s some sort of official communication that never tells them anything that they haven’t known for weeks, and tosses it into the dustbin. And as far as Mr Spring is concerned, objective accomplished. He can prove that he is a director of a registered company, even though—’

‘I get it,’ I said. ‘Why aren’t you a bit more careful? More suspicious, more stringent?’

‘Because we can only do those checks that the law requires,’ said Rowe, ‘and this law was made in 1856.’

‘In an age before fraud, theft and embezzlement had been invented. This country’s all history,’ I said.

‘And the story goes on. The purported new director takes the stamped and sealed confirmation into any bank he likes the look of, and he opens a business account. And with that, if anyone sends him a cheque, he can cash it. And that also saves him the embarrassment of having a pile of money hidden in a saucepan when the Police arrive.’

‘As we will,’ I said.

‘I rather think’ said Mr Rowe, ‘that’s everything this annual account tells you.’

‘We’ll arrive all right, but we won’t arrive yet,’ said Jane. ‘If we close his bank account, he’ll notice. He’s sure to go to ground.’

‘He already did,’ I said, ‘and our job is to do some digging.’

That evening, Jane and I were sitting together in my office.

That evening, Jane and I were sitting together in my office.

‘Would you like to spend some time together in the Sandringham?’ Jane asked. ‘Tomorrow’s Saturday. We can stay in bed for as long as we want to.’

‘There’s nothing I want to do more,’ I said, ‘because I still haven’t recovered from the jet-lag.’

‘I’m pretty sure I can find something that will interest you,’ Jane said, correctly, ‘and you won’t need to get out of bed.’

Jane and I left the Police Station hand in hand, climbed into the car together and drove roughly in the direction of the Sandringham, but Jane thought it would be more relaxing for both of us if we parked on one of the paths across Queen’s Meadow and worked off some passion in the back seat.

‘Your head is still full of fake telephone numbers, disappearing offices and a strange man who leaves boxes of chocolates for women he’s never met,’ Jane said. ‘I know how to take your mind off all that and let you see the job in perspective.’

Gently, whispering ‘This time, leave it all to me,’ she made love to me. After that, Jane seemed more important than the job. There would be other jobs. At least, I hoped there would be other jobs, but there would never be another Jane. I wondered where she gained her extraordinarily detailed knowledge.

‘I’ve never read so much as a self-improvement book on how to do sex better,’ she confided.

‘You could write it,’ I said, ‘and you’ll be on the front page of the

TLS

by this time next week.’

‘No, I couldn’t. I just… I just love you. The rest all comes by instinct,’ she smiled, ‘and anyway, you can do it too. Nobody ever made me feel so happy, safe, good.’

‘Are you serious? You know I’m an old man, tired and weak.’

‘No,’ said Jane, ‘but if you sing the verse, I’ll join in the chorus.’

‘What? Can you explain?’

‘I mean you’re fifty and you’re the best I’ve ever had.’

We sat on the front seat on the car and we held each other close. We drove off towards the Sandringham.

That night, in bed, reassuring me, Jane told me again that she loved me. Nobody except my mother had ever told me that before. I held Jane close. Strange to say, it wasn’t the lust that made me feel so calm and happy. It was that sense of being close, joined together, that I don’t think I ever felt before.

Jane decided that I should see some of the sights of Edinburgh while I was working there.

Jane decided that I should see some of the sights of Edinburgh while I was working there.

‘Heads or tails?’

She flipped an imaginary coin, caught it on the back of one hand and covered it with the other. I called ‘Heads.’ Jane uncovered the coin and told me we were going to spend the morning in the castle, and ‘The Loch Ness Monster can wait until tomorrow.’

‘How many times have you seen the Loch Ness Monster?’

‘She keeps herself to herself,’ said Jane. ‘I’ve seen her, but only in faked photographs and once I heard her on sonar — and even that was on the wireless.’

I could scarcely believe what Jane was telling me. ‘The Loch Ness Monster is a lady?’

‘Definitely. Probably the most powerful lady in the whole of Scotland,’ Jane smiled, ‘apart from the Queen, of course.’

We spent about two and a half hours looking around Edinburgh Castle. I never saw such a handsome Army base and housing estate, with a fine view of the sea in the distance. Mind you I couldn’t see how a tank battalion could have got out through that narrow arch.

‘The inlet there is a natural harbour,’ said Jane, pointing into the distance. ‘See? A hundred years ago, the water would have been bristling with the King’s ships.’

‘Going where?’

‘Wherever they were needed. All over the world. Australia, India, Africa, South America.’

We walked through the gate, out of the castle, downhill towards the city.

We walked through the gate, out of the castle, downhill towards the city.

‘Gosh,’ I said, ‘you mean, this castle is pre-war? Pre-first world war?’

‘Sam,’ Jane explained with a broad grin on her lips, ‘this castle is pre-America.’

‘Shouldn’t they have build it nearer the stores?’

‘Well…’

We heard a sudden, tremendous, explosion behind us, like a grenade going off.

‘Gunfire!’ I yelled, as the bang echoed around us. I threw myself onto the sidewalk, grabbing Jane’s arm so as to pull her off balance. If she was standing up, she was a target. She landed beside me. ‘Roll away from the traffic,’ I yelled, ‘you’ll be safer if you lie close to the wall. And don’t move.’

A moment later, I noticed that nobody else had ducked out of the way, and I yelled, ‘Get down! Get down, people!’

‘We’re perfectly safe, Sam,’ Jane said. ‘and so is everyone else. Help me up.’

‘We’re under fire, Jane. Don’t you know what that means?’

‘It means you don’t know about an old Edinburgh tradition, Sam. Here, help me up.’

‘We’ll be shot.’

‘Sam, it’s the one o’clock gun. It’s the cannon that you were looking at half an hour ago.’

‘Sam, it’s the one o’clock gun. It’s the cannon that you were looking at half an hour ago.’

‘Was I?’

‘It’s not aimed at you, nor at anybody else. They fire that gun on the stroke of one o’clock.’

‘Oh,’ I said as realisation dawned on me. ‘That gun.’

I stood up, grabbed Jane’s arm and pulled her upright.

‘Are we a long way from the car?’ I asked. ‘My clothes got a bit dusty. If we went to the Sandringham, I could give them to the laundry and change into a clean outfit. While I’m there, I shall wipe the egg off my face.’

‘I’m not surprised that you got dirt on your clothes,’ Jane said. ‘I got some mud on my coat, too, and some bruised ribs as well. We’re not far from the car. We’re on the Royal Mile. Lots of little shops all crowded together. The car is a couple of minutes’ walk away, but I think you need to sit quietly for a couple of minutes before you get behind the wheel.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I need to relax. I’m still shaking. I must have looked a fool.’

‘Oh, look on the bright side.’ Jane squeezed my hand. I turned towards her and she kissed me. ‘You showed everyone what to do if a gunfight starts. That could save someone’s life, especially if the English invade. Why don’t we sit in that coffee-shop over there and cool off a bit.’

‘Oh, look on the bright side.’ Jane squeezed my hand. I turned towards her and she kissed me. ‘You showed everyone what to do if a gunfight starts. That could save someone’s life, especially if the English invade. Why don’t we sit in that coffee-shop over there and cool off a bit.’

‘Do they have Viennese coffee?’

‘Quite possibly. They might even sell Coca Cola. There’s only one way to find out.’

We sat together in a dimly lit corner. Jane went to the counter and asked.

‘They have both,’ Jane reported back. ‘Viennese coffee and Coca Cola. It’s a miracle. Somebody tell His Holiness.’

When I took a first sip of the coffee, I felt better already. ‘Jane,’ I asked her, ‘do you really think the English are going to invade?’ I asked.

‘I’d say it was unlikely, as they haven’t invaded Scotland since the middle of the sixteenth century, but it always helps to rehearse. You’ve shown me what to do if they return and charge the crowds on horse-back with banners waving and swords lashing out. I know what to do if they open fire.’

‘Practice makes perfect,’ I said.

We left the café and we walked farther down the Royal Mile. I looked along the line of small shops opposite and I noticed one called

International News.

We left the café and we walked farther down the Royal Mile. I looked along the line of small shops opposite and I noticed one called

International News.

‘Do you think they might have

The New York Telegraph?’ I asked Jane.

‘Are you homesick already?’

‘No, but I want to know who won the hockey game.

If the Rangers won, then I can pay the phone bill.’

‘Well, looking in the window, I can see they have

Le Monde, Der Spiegel, Pravda and something in squiggly writing that I can’t read, so it looks worth trying.’

They say you only know there’s a God because of the co-incidences.

They say you only know there’s a God because of the co-incidences.

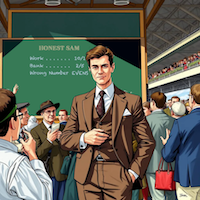

Inside the shop, four or five customers were browsing the newspaper racks. At the back of the shop, bringing in some cartons through a back door, was the man I most wanted to talk to. He was looking now at the carton he was shifting, now at whatever was on the other side of the door. If they’d let me have a gun, I would have drawn it. I was lucky. So far, he hadn’t recognised me. And he probably didn’t have a gun either.

Behind the counter, the shopkeeper was a man who might have been sixty years old. Grey hair, grey moustache, short and stocky, pale brown overalls. Like everyone in the newspaper industry, he was unshaven and he had likely been awake since midnight, receiving the latest papers and setting them out on the racks. Just by looking at him, you could see there was nothing about the newspaper business that he didn’t know by heart.

‘Jane,’ I muttered, ‘can you create a diversion?’

‘When? Now?’

‘Yeah. Distract that guy at the back of the store. I want to see his face, and I don’t want him to notice mine. Get him to look at you. Go for it.’

‘Certainly, Sam,’ she said, smiling. ‘I have an idea. I’ll take all my clothes off. How would you like that?’

‘I’d like it a lot, but can you think of another idea, instead?’

‘That may take a while.’

Jane walked up to the counter and asked the shopkeeper, in a voice loud enough to be heard on Mars, ‘Is the Christmas issue of Pure in yet?’

‘Everybody looked at Jane as the shopkeeper picked up the magazine from behind the counter and put it down in front of her.’

‘Do you mind if I look at the centrefold? Just a look and then I’ll give it back. They’re always so beautiful.’

‘The public library is on Mountbatten Bridge,’ said the old man, who was obviously used to being mistaken for Freebie Central. ‘In here, that magazine costs one shilling.’

Jane, who had several shillings in her purse and would have claimed the magazine on expenses anyway, protested noisily. ‘I only want to look at it!’

We had a diversion in progress. It was most effective.

Jane picked the magazine up and made a feint of trying to open it. The shopkeeper snatched it out of her hands. Then, in a masterpiece of improvised theatre, Jane gripped her left middle finger in her right hand and yelled blue murder.

‘Aaah! That’s the finger I dislocated! You—’

‘Sorry. I didn’t mean to hurt you. Just defending the shop’s property.’

The ruse worked. The man at the back of the shop was watching the argument open mouthed. I saw his face clearly. Joshua Spring. Mr Spring recognised me, dropped the carton in a crash of shattered glass, wheeled around and disappeared through the open back door. That’s what happens if you don’t have a gun.

Jane was clutching her finger and wailing in agony.

‘Here,’ I said to the shopkeeper. ‘I’ll pay for the damage.’ I had no idea what a shilling looked like, so I took all the coins out of my pocket and held them out to him in the palm of my hand. ‘Is any of these a shilling?’

He found a silver coin and took it.

‘That guy who ran out the door,’ I said, ‘is that Joshua? I think I know him.’

‘Joshua Spring.’

‘Yeah, that’s the man. He wrote to me recently and told me that he’d found a job. This must be the job he found,’ I said.

‘You know him?’ the shopkeeper asked.

‘Oh, we met a couple of days ago.’

‘He’s

on the lump,

’ said the shopkeeper. ‘He’ll work here, cash in hand, for a few weeks. Then he disappears and two or three months later, he comes back.’

‘I’d like to see him again before I go back to the States.’

Jane was still clutching her finger and yelling, so I said, ‘That’s a bad injury you’ve given yourself, honey. I’ll give you a ride to the

E. R.’

The shopkeeper told me what I already knew. ‘It looks to me as though Josh doesn’t want to see you.’

‘It’s a long story. If you wanted to find him, where might you look?’

There was a handwritten note pinned to the wall. The shopkeeper turned around, pulled the note off the wall and gave it to me.

‘One of these places,’ he said.

‘May I borrow this?’

‘Of course.’

‘And do you have the New York Telegraph somewhere?’

‘Over there. Half a crown.’

‘Half a crown?’

‘Yes, sir. Air freight is pricey.’

‘Oh, I’m not complaining about the price. I’m asking what half a crown means.’

Again I took all the coins out of my pocket and offered him the choice. He took two coins, put them into the cash register, and put three coins back into my hand, saying,

‘One and six change.’

I found the paper. ‘Come on, Jane, you’ve suffered enough already. I’m parked outside. I’ll take you to the hospital. Hope you’ve got Blue Cross.’

‘I take it everywhere I go,’ she said, ‘despite not knowing what it is or what it’s for.’

We left the shop together. Jane stopped clutching her finger. ‘It’s all right, Sam, I was faking it. You asked me to create a diversion—’

‘You did good. Grace Kelly herself couldn’t have acted better.’

We sat in the car and I leafed through the newspaper.

Jane asked me, ‘How did the Rangers get on?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘This is Tuesday’s paper. Half a crown wasted, whatever that is.’

‘Thirty-five cents,’ said Jane.

‘Do they have tax deductible investments in Scotland?’ I asked.

We were in the Sandringham. We spent a warm and loving night, and we awoke in each other’s arms, holding each other close. The sun was rising. In this part of the world, that’s about nine o’clock.

We were in the Sandringham. We spent a warm and loving night, and we awoke in each other’s arms, holding each other close. The sun was rising. In this part of the world, that’s about nine o’clock.

‘Morning, lover.’ Jane’s voice was a perfumed whisper. ‘Want to make love again?’

‘That’s the best idea I ever heard,’ I said.

When we awoke, the day outside was bright and looked cold. I wasn’t sure that I could untangle myself from Jane. I only wanted to cling to her.

‘Here,’ said Jane. ‘This is what I bought in

International Newsagency.

I thought it might interest you more than the

New York Telegraph.’

The December issue of Pure was on her bedside table. She reached it to me.

‘Why would I want this, when I have you?’ I asked as I struggled to sit up and look at it. ‘This is for when you’re desperate for a girlfriend and you haven’t got one.’

‘You want it because you like looking at pretty ladies. Don’t be afraid to admit it. I’d much prefer a boyfriend who likes to look at women to one who doesn’t. Besides, look at the front cover.’

‘Should I recognise her?’

‘Yes, because she’s Catríona Murray. So there are probably pictures of her in there somewhere.’

I opened the magazine at random and I saw pictures of a woman who wasn’t Catríona Murray.

‘She’s beautiful,’ I said.

‘See? I told you that you like looking at pretty ladies. Is that Catríona?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I met Catríona. I’d recognise her. This is Salomé, at least according to the caption.’

‘You should look at Catríona because she’s one of the victims of the break-ins.’

‘OK,’ I said, ‘let’s see whether we can learn anything from her photos, other than what she looks like with nothing on.’

I turned to the contents page.

|

The Girls

|

|

Bathsheba by Rhoda Wright

|

page 6

|

|

Salomé by Jacob Glover

|

page 9

|

|

Catríona by Christian Rose

|

page 10

|

|

Candace by Rhoda Wright

|

page 22

|

|

Amethyst by Rhoda Wright

|

page 24

|

|

Tiffany by Christian Rose

|

page 30

|

|

Susanna by Jacob Glover

|

page 38

|

|

Honor by Candace Yates

|

page 43

|

So I turned to page 10, and there was Catríona. She was pictured in a bikini on a yacht, in her hotel room wearing a negligée and in her underwear in front of a diorama, a featureless coloured wall which could be found in pretty much any photographer’ studio.

So I turned to page 10, and there was Catríona. She was pictured in a bikini on a yacht, in her hotel room wearing a negligée and in her underwear in front of a diorama, a featureless coloured wall which could be found in pretty much any photographer’ studio.

Jane took a look at her and said, ‘Have you ever kissed a woman with that much lipstick?’

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’

‘Do you like kissing a woman who’s wearing lipstick?’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Yes. It feels nice.’

‘I brought some tulip red Elizabeth Arran,’ said Jane. ‘We’ll enjoy that together.’

‘I still have to scour this magazine for evidence,’ I said, ‘starting at the beginning.’

‘That’s all right,’ said Jane, ‘as long as you don’t pretend that you aren’t enjoying it.’

I looked at the front cover again. Then I opened the magazine and I saw the contents page again.

‘Eight ladies, listed in no order that I can see, and probably all with fake names,’ I said.

‘Let me see.’

Jane wriggled across the bed so that she could look at the names of the women.

‘Well, now,’ she said, ‘look at that.’

‘What have you noticed?’

‘The name’s the same. Tiffany. One of our victims is called Tiffany.’

‘Lots of women are called Tiffany,’ I said. ‘She ain’t necessarily the same one.’

We turned to page 30. There was Tiffany: older than Catríona but not much, long black hair, sultry, the girl who lived in the leafy suburb and always came top of the class. She posed in a dress store, in what looked like a hotel lounge, and on the inevitable yacht.

‘Want to know what I think?’ I asked Jane.

‘You’re thinking that it’s the same yacht.’

‘You’re right.’ As I looked at the pictures, the obvious dawned on me. ‘It is. The light, the contrasts and the shadows, are the same, so the pictures were taken at the same time of year. And look at the scenery. That’s the same, too. Same yacht, same place.’

‘Same photographer,’ Jane put in. ‘Christian Rose.’

‘I bet he doesn’t mind getting up and going to work in the morning.’

‘Does all that tell you anything?’

‘It tells me the same as it tells you, Jane. Two of the victims, Catríona Murray and Tiffany Walters, were on the same boat at the same time, posing for a photographer called Christian Rose.’

‘Anything else?’

‘I’ll bet the farm,’ I said, ‘the boat was the M. V. Clu… something or other.’

|

|

Jane’s granny shoots a tin of beans off a fence-post

|

Jane filled in the missing words for me. ‘Cluaran an Luchd-siubhail. It means

Rusty Bathtub.

‘Really?’ I asked. ‘Somebody called his yacht the Gaelic for…’

‘No, not really,’ said Jane. ‘It means The Traveller’s Thistle.’

‘Where the devil did you learn that there Injun talk?’

‘Inherited privilege, Sam. My granny came from Harris. She never spoke a word of English.’

‘Did she wear a feathered head-dress and cut the heads off neighbouring tribes-people with a tomahawk?’

‘No, she spent most of her time cutting peat and tending potatoes, but she was a crack shot with a bow and arrow. She could shoot a tin of beans off a fence-post from a hundred yards.’

‘How about two hundred?’

‘Harris isn’t that big.’

Jane suggested we have a look at the passenger manifest of the M. V. whatever-it-was and see who else was on it. If the vessel was abiding by the law, the master of the vessel — how I loved the antique language of Scottish maritime law — would have left a list of his passengers and his route at the harbour-master’s office in Portree. That wouldn’t tell us who the crook was, unless he’d signed it with his real name and paid the fees and charges with Diner’s Club, but it might tell us who the victims were. The fly in the ointment was that the only place where that list could be found was the harbour-master’s office in Portree, getting on for three hundred miles away to the north, in a country with a famously inhospitable north.

Jane suggested we have a look at the passenger manifest of the M. V. whatever-it-was and see who else was on it. If the vessel was abiding by the law, the master of the vessel — how I loved the antique language of Scottish maritime law — would have left a list of his passengers and his route at the harbour-master’s office in Portree. That wouldn’t tell us who the crook was, unless he’d signed it with his real name and paid the fees and charges with Diner’s Club, but it might tell us who the victims were. The fly in the ointment was that the only place where that list could be found was the harbour-master’s office in Portree, getting on for three hundred miles away to the north, in a country with a famously inhospitable north.

‘Three hundred miles,’ I said, ‘that would be five hours or so on the freeway, wouldn’t it?’

‘Freeway?’

‘Yeah. A place that far away, there has to be a freeway — right?’

‘Well… not really. We won’t get to Portree on a Sunday,’ said Jane.

‘The Wee Frees

would be absolutely boiling under the collar if we could. The Highlands are closed on Sundays, including the buses and the ferries.’

‘How about the car hire firms?’

‘That’s an excellent idea, but they too are as shut as a Sunday school on Wednesday, I’m afraid.’

‘So,’ I asked Jane, ‘how are we going to get there, and when?’

Jane had a great gift for geography. ‘We can go tomorrow.’

‘Monday.’

|

|

What happens when the Wee Frees see someone driving a car on Sunday

|

‘Yes. Train to Kyle of Lochalsh, then there’s a ferry-boat to Kyleakin, and after that there’s a bus to Portree. I'll book a double room for two nights at the Duke’s Hotel.’

‘Won’t the Wee Frees be annoyed about the double room?’

‘They’ll go berserk,’ Jane laughed, ‘just wait and see. They haven’t even got over the Duke’s selling alcohol. Meanwhile, how would you like to spend today seeing the Queen’s house in Edinburgh?’

‘That would be better than working,’ I said, ‘if the house is open and especially if we can drive there. Let’s do that.’

‘Okay, big boy, but don’t let the Wee Frees catch you driving a car on the Sabbath day,’ Jane advised.

‘Do they station a battalion here?’

‘No,’ said Jane, ‘they start at about Perth.’

We wandered through Holyroodhouse for three hours. I was very impressed. I’d never seen anything like the sheer beauty of it.

‘Those rooms… I’m sure Eisenhower’s envious,’ I said as we left. ‘Kings and queens must have been really, really important.’

‘Of course the Queen’s important,’ Jane explained, sounding a little more irritated than I thought necessary, ‘She’s the Queen. She’s the most important person in Scotland. That’s what “Queen” means.’

‘That’s why you don’t need a president, I guess. The place is so old, I wonder it hasn’t fallen down.’

‘We look after it, Sam. The Queen needs a place to live when she’s here.’

‘And it’s so big. A huge place.’

‘They built outwards because they couldn’t build upwards. The electric lift wasn’t invented until 1852.’

‘How do you know all that?’

‘School project.’ Jane smiled at the memory of her attempt at architecture appreciation. ‘When I was about ten, the school made us write two pages about Holyroodhouse. I remember it took ages. I borrowed the guide-book from the library and copied it until I’d filled two pages and I had sore fingers afterwards. I got six out of ten.’

‘Six out of ten — way to go!’

‘Not really. It’s a fail mark.’

We were driving back to the Sandringham, along Laurence Street, and Jane was telling me that she didn’t want to live in a house like Holyroodhouse because she didn’t want to be endlessly surrounded by fawning servants, and I was telling Jane that I’d bet the farm she’d live there if the chance came her way, when the knob came off the gear-shift. A minor problem but, fortunately as it happened, it needed to be fixed, so I pulled over to the kerb. I spent a couple of minutes trying to screw the knob back onto the stick, but the thread was cracked and I couldn’t get it to stay in place.

I explained the problem to Jane and I asked her whether she thought it was safe to drive the car.

‘Probably,’ she said, ‘but there’s a shop over there that sells car parts. Why not ask them if they can replace it?’

‘On a Sunday? What will the Wee Frees say?’

‘There’s an “Open” sign on the door, and the Wee Frees are all in Church because it’s the Sabbath day, so be quick and leave before they find out and surround the place.’

‘Where is the shop?’

‘Two doors along.’ Jane pointed. ‘Green paint.’

‘Give me two minutes.’

I wandered over to the shop. It was small, one door and one plate-glass window, and painted above the window,

Fix A Car in yellow lettering. Hard to get spare parts our speciality.

When I looked in the window, I saw a lady I recognised. She was tidying up around the counter and the cash-till.

I came back to Jane’s side of the car. She sensed — by Police instinct, I guess, or maybe I already had that expression of grim determination on my face — that something was up.

‘Jane, tell me,’ I kept my voice down, ‘how much Police training have you had?’

‘The minimum. I’m a Special. I can look after myself, blow a whistle, arrest people and stand on the touchline of a football match looking out for anyone throwing an empty beer bottle.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Anything else?’

‘No, that’s it, except that I used to watch Here Come the Rozzers on telly.’

‘That’ll do me. You and I are partners for the duration.’

‘Oh. Wonderful. What are we going to do?’

‘Keep out of sight and stand by the gate,’ I said. ‘The back doors of the shops along here lead to that gate. If a woman comes running out, get her into the back seat of the car. If she’s who I think she is, she and I ought to have a little chat.’

‘Yes, sir. I’ll change into Super-rozzer immediately. Just one thing, Sam, supposing she isn’t who you think she is?’

‘Then I buy a new knob for the gear shift, pay three and sixpence and wish her a pleasant afternoon.’

‘Three and sixpence?’

‘I agree it’s only worth fourpence halfpenny, but she has to make a living.’

A bell tinkled as I opened the door of Fix A Car. It was a dim and dingy place with dusty boxes of parts on every hand, and most of them looked as though they had been there since before the War. The shopkeeper turned to look at me, and I asked if she had a gearstick knob like the one I was holding.

A bell tinkled as I opened the door of Fix A Car. It was a dim and dingy place with dusty boxes of parts on every hand, and most of them looked as though they had been there since before the War. The shopkeeper turned to look at me, and I asked if she had a gearstick knob like the one I was holding.

‘Ford Prefect,’ she hazarded.

‘Close, but no cigar,’ I said. ‘Jaguar Mark One.’