All aboard

The Flying Plutonium

Today was such a big day that four Press photographers took pictures and shot films of us as we stood in the gloom outside London Parkway station. We were a small crowd, fifty people, I guessed, probably the most passengers the station had ever seen for a single train, waiting in the street for the grimy wooden doors to open, looking at our watches and at the station clock, listening nervously for the growl of a diesel motor pulling an empty train away into the distance before we intending passengers had been allowed near it. The train was supposed to leave at ten o’clock, but already the clock was showing ten minutes past. So far, we had not heard any departing train, but we had not heard any announcement either.

Today was such a big day that four Press photographers took pictures and shot films of us as we stood in the gloom outside London Parkway station. We were a small crowd, fifty people, I guessed, probably the most passengers the station had ever seen for a single train, waiting in the street for the grimy wooden doors to open, looking at our watches and at the station clock, listening nervously for the growl of a diesel motor pulling an empty train away into the distance before we intending passengers had been allowed near it. The train was supposed to leave at ten o’clock, but already the clock was showing ten minutes past. So far, we had not heard any departing train, but we had not heard any announcement either.

When at last a man in his fifties and a blue railway uniform opened the door to admit us, he shouted over the traffic noise that he was Fred, he was the Station Master, and he was sorry, Joe had left the key in his desk and not told anybody where it was. The train at Platform Three was the Flyin’ Plutonium, the ten o’clock for Pluto. The inbound service had been delayed by star-dust on the rails and Planetary Railways apologised, et cetera. He actually said ‘et cetera.’ ‘It’s over there,’ he pointed, ‘have yer tickets an’ passports ready.’

An ungrateful fellow whose voice came from an affluent boulevard lined with mansions, Bentleys and yachts, who carried a furled umbrella and wore a clerical collar said ‘Ah, it’s the Fat Controller,’ and Fred, well used to that and similar unoriginal jibes, said that he’d never controlled so much as a pork sausage in all his life.

‘But you have been fat,’ I said before I had time to stop myself.

‘Well, that’s because since I joined the railway back in nineteen seventy-four,’ Fred said, ‘I’ve worked on this here station, and the only thing I’ve had to do is to put the clock forward in Spring and back again in Autumn. The ’ardest bit is climbin’ up the ladder. Eatin’ sort of passes the time, don’t it. Digestive biscuits passes it best. Over there now, Platform Three. You can’t miss it. Not unless you haven’t got on the train when the doors close.’

Built in the late nineteenth century, London Parkway had been Town Hall Woolwich station, three platforms at the western end of the Woolwich and Tilbury Railway, and had fallen derelict when the service was closed in the middle 1960s, confronting its passengers with the stark choice of buying a car, or taking two very long bus rides every working day, or spending the rest of their lives with no income lying on the sofa and watching daytime television.

When the Planetary Railway needed a terminus for their Outer Planets Line, they bought the derelict Town Hall Woolwich station for a pound and hired a team of builders to re-furbish it. Apart from changing most of the nameplates to London Parkway and sticking timetables on top of the Capstan Cigarette advertisements, the builders had done little. The place was dingy and grubby and smelled of smoke and mud and rotting timber. So murky was the murk that you could almost see the London suburban services of sixty years ago, the Jazz Trains, letting off steam or setting off for commuter land Essex, then all green fields of cabbages and happy milkmaids and chocolate box cottages, as departing passengers slammed the doors and the Guard waved a green flag and blew on a whistle, and the arrivals fumbled for their tickets and complained about the train being late and the mud being on their expensive shoes. These were City jobs they were heading for, bowler hats and Kerberry raincoats were de rigueur, and they could be summarily dismissed for stubble or muddy shoes. That shirt you are wearing has pockets, Johnson. You’re fired.

Sixty years after it was last trodden in, the mud was still there. Only after signing the contract had the builders discovered that Town Hall Woolwich had been Grade A Listed and any building work greater than replacing a broken window needed planning permission, which took a long time and cost a lot of money, especially when you added on the hundreds of pounds needed to bribe the desk jockeys in the town hall next door to issue the requisite papers.

Even screwing the new glass fibre name-plates on top of the old wooden ones drew a teenage lad with a clipboard and a hard hat to take photographs and promise to get back to them. He never did, of course. He was hoping for a bribe. They didn’t give him one because instead of the usual charcoal grey Council issue suit, he was wearing a blazer embellished with the badge of Woolwich Drama School.

We walked to Platform Three as quickly as we could without looking panicked, expecting the train to drive off before we reached it, as buses always do. A tall, fragrantly perfumed and seriously elegant middle aged woman in a chequered white and black coat of the kind that I couldn’t afford for my wife, or for anyone else’s wife, if I saved every spare penny for a hundred years asked, ‘Excuse me, I didn’t hear what he said. Do you happen to know where the train to Pluto is?’

‘Just there. They’re loading newspapers into the luggage space.’

She paused and smiled at me. ‘I thought I was going to miss it.’

‘The god of railways smiles upon you,’ I said, imagining a transfigured Isambard Kingdom Brunel sitting on a cloud in a dramatic pose and hurling a bolt of points failure just in front of Platform Three.

Between us and the nearest doors of the train, two parcels handlers were energetically stacking supplies into the parcels space at the back of the train. Tinned food, spare parts for something, loaves of bread, cigarettes, newspapers. I was impressed by how easily they could lift bundles of newspapers that probably weighed the same as me. News of the Earth, they said, and the front page story was not First trip for The Flying Plutonium but King signs Kingdom of East Bog-hole into British Empire, more important, but less interesting. There never were many Kingdom spotters.

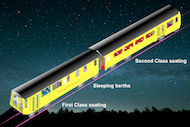

She joined the train just ahead of me. The train turned out to be a sleek, boxy affair. The carriage closest to us was end to end second class seats and the farther carriage contained a a handful of first class seats and a few sleeper berths. Having a first class ticket, I picked a comfortable seat, covered in sumptuous blue moquette. My travelling companions for the next twelve hours would be the clergyman, the lady in the expensive coat, a young couple whose suitcase, daubed Just Married in white paint, lay on the luggage rack above their heads, two earnest looking young women who might have been students of mediæval French literature but probably weren’t, and a man in a black leather jacket who had been out on the platform taking pictures of the train and wasnow setting out on the table in front of him several cameras and a sound recorder.

Last to join the train were three squaddies, probably from the Royal Artillery Barracks down the road.

On the platform Fred blew a whistle and waved his arm. ‘Sorry, Dave,’ he shouted, ‘God alone knows where Joe’s put the green flag.’

The warning sounded (‘Mind the doors, please!’)

and the doors closed with a reassuring

thunk.

The warning sounded (‘Mind the doors, please!’)

and the doors closed with a reassuring

thunk.

The heating began to whirr and I felt hot air start to blow out of the grilles in the floor and onto my ankles. Then the driver played the first four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony on his two-tone air horn and the train started to move. I was expecting the engine to make enough noise to wake the dead and shake the train like a baby’s rattle, but it was much quieter than the usual cheap-jack diesel engine, and the train moved as smoothly as though the driver had forgotten to apply the brakes and the train was quietly coasting downhill. Or maybe the first class compartment was double glazed and fitted with Rolls Royce suspension.

There were two indicators attached to the ceiling and a message began to scroll along one of them.

I found myself reading the scrolling messages over and over again, even though I had seen every one of them elsewhere.

The second indicator displayed a message in the

lingua franca

of the outer planets:

‘Driver speakin’. ’

A loudspeaker somewhere closer than necessary to my left ear started talking.

‘I’m Malcolm. This is the ten o’clock service to Pluto, the Flying Plutonium. We are running about half an hour late.’

I felt my inside pocket to make sure my passport was still there. It was. Elegant Lady looked into her Louis Vuitton handbag, Leather Jacket Man looked in his camera case, Clergyman turned his attention from Just Married Couple for a moment and checked that his documents were still piled flat on the table in front of him. French Literature Students searched their blazer pockets and eventually found everything. Just Married Couple didn’t bother looking.

‘Do you still have that red ticket?’ Just Married Wife meant the sleeper reservation. ‘Let’s pretend we need to hide from the ticket inspector.’

They stood up, man-handled their suitcase off the rack, walked to their sleeper and locked the door behind them.

We had been travelling along the former Woolwich and Tilbury for a quarter of an hour or so. The view out of the rain-spattered window was of dull weather, housing estates built a hundred years ago, fields of mud and bare trees.

‘Elevenses,’ said a voice behind me. A young woman in a railway uniform, rattling a trolley load of plastic lunch boxes, miniatures and quarter bottles, put a lunch box onto the table in front of me. On her blue beret the chromium plated

Planetary Railways

roundel flashed in the sunlight.

Pick a bottle, any bottle you like. I took mineral water, and Stephanie went off to feed the other passengers. She must have felt as though her job was giving plastic envelopes of minced fish to a room-ful of cats.

Clergyman asked for a double Highland whisky. Stephanie removed the caps from two miniature bottles, explaining, ‘The licensing laws mean you can’t take the bottles off the train, so I have to take the top off before I give it to you, just to make it more difficult.’

‘Malcolm speakin’. ’ The loudspeaker came back to life. ‘If you haven’t travelled on this line before, look out of the windows for the next five minutes.’

There was a shock of raised air pressure as the train entered a tunnel. My ears popped, even though the train wasn’t going particularly fast. I was staring through the window at the blackened brick of the tunnel wall and thinking that there wasn’t really all that much to see and I might be better off opening the plastic lunch box before it cooled when, a few seconds later, the train came out of the other end of the tunnel, the carriage fell almost silent and the countryside was gone. On the other side of the windows, where there used to be houses and streets and trees and hills and fields and an endless line of telegraph poles, there were darkness, stars and planets. Everyone gasped, including me — I almost dropped the water. The train was rolling through space.

Uranus, the teal blue planet with faint rings, lay in the far distance dead ahead, looking the size of a football. I heard Elegant Lady breathe, ‘Wow… it’s beautiful.’

Two more soldiers came in after him and the three of them took up the seats around the table which Just Married Couple had left. Ginger Squaddie took a pack of cigarettes out of his pocket and flipped the lid open, offering them around.

Clergyman lowered the book he was reading. ‘Please don’t smoke,’ he said, ‘it makes us cough. There’s a smoking area somewhere.’

The three of them were silent for a while. I realised I hadn’t taken the lid off my elevenses yet. It was sliced turkey, mashed potato, peas, gravy and a plastic fork. Most people sneer at railway food but this was good. Thank God they fired Prue Leith. It irked me that the food was better than I could have cooked by myself in my own kitchen.

East London Squaddie broke the silence. ‘What are we going to do when we get there, sir?’

There was another silent moment. I ate a fork-load of peas.

Conversation broke out among the Army contingent again. Private McGovan wanted to know,

‘Which side are we on?’

Stephanie appeared again and offered the lads something to eat. ‘Sorry, I didn’t see you there.’

As Stephanie set about opening the bottles, she observed, ‘I overheard that you lost a colleague. I’m sorry.’

Elegant Lady became agitated. ‘There’s only one television shop on the Plumstead Road and that’s Kelly’s Tellies.’

One of the French Literature Students went to find the first aid kit as Elegant Lady drew breath and continued loudly, ‘Where’s Dave? Where’s the Senior Conductor? Why isn’t there ever a Senior Conductor around when you need one?’

The door to one of the sleeper berths clicked open. Still half asleep, Dave put his head out. ‘What’s going on?’

French Literature Student came back to the group. ‘The first aid kit is empty,’ she reported. ‘I brought wads of paper towels. Best I can do.’

Elegant Lady could be heard indistinctly shouting at Dave, who seemed to be trying, with limited success, to calm her and get her story straight.

Peace returned in First Class. For the next hour and a half we were travelling through space with the teal blue planet ahead of us, its great moon, a thousand miles across, to one side. The view changed little as we forged ahead. We passed an occasional signal, we outpaced a comet that was rushing back towards its remote home sun in deep space trailing ice and flames, we passed a goods train carrying rare mineral ores towards the Earth and we were jolted awake by the horns and bells of a level crossing, but the stars, light years distant from the track, appeared to be standing still in the sky the whole time. Stephanie brought hot cups of tea, the squaddies talked quietly about their mission and Ginger Squaddie mopped up the blood on his face, Clergyman fell asleep with his nose still in his book, French Literature Students stared out of the windows at the cosmos, and Elegant Lady was sitting in some other part of the train, out of sight of the soldiers and slowly recovering her composure.

‘Malcolm speaking.’ The loudspeaker broke the silence again. ‘The train will be on Uranus in about ten minutes. If you are leaving the train here, please make sure you take all your luggage with you and have your ticket and passport ready for the automatic barriers. If you have a multi-planetary watch, set it for Uranus. The time is 12:48 and it’s Lokisday the sixteenth of the fifth month. I think that’s everything. Thank you for travelling Interplanetary. Uranus in ten minutes.’

‘This is Dave, the Senior Conductor speaking. The station master on Neptune reports that there is heavy gun-fire close to the station and services to Neptune are cancelled for the moment. This train is being diverted and will not call at Neptune.’ There was an enormous groan from the passengers and cries of ‘Bloody railways,’ ‘Bloody typical’ and ‘It’s supposed to be a railway, not a mystery tour,’ even from passengers who weren’t going to Neptune anyway, and the conductor waited for the moaning to die down. ‘Passengers for Neptune may leave the train here and either wait until HQ organises a replacement bus to Neptune, or go back to Earth on tomorrow’s train. Keep your tickets because you’ll need them to claim a refund. Thank you.’

As the complaints continued (Bloody inconvenience! Bloody unions! Bloody nationalised industries, etc.) Dave added as an afterthought, with creditable good humour, ‘I am not responsible for West Bog-hole invading East Bog-hole. I only check the tickets and Malcolm only drives the train. Thank you.’

‘Yeah, and us — round the bend,’ someone yelled.

A middle-aged man in a khaki Army uniform stepped off the platform into the First Class compartment. He was carrying a golf club and a crinkled telegram. ‘I’m after Corporal Jacquard, Private McGovan, Private Blenchard, is that you over there?’

He followed the soldiers off the train as a couple who appeared to be in their middle sixties came into the compartment from the Second Class end.

‘Are there any empty seats in here?’ the man asked. He spoke in a New Zealand accent and wore robust black shoes, a dark red overcoat and a brown trilby. The woman with him wore a black woollen bobble hat, a thick black puffa jacket and heavy hiking boots.

The couple looked at the seats as though they thought the seats might be on fire or covered in glue. When they had satisfied themselves that the seats were safe and hygienic enough to be sat on, they put their case in the luggage rack and sat down together. ‘Golly,’ said Bobble Hat in the same New Zealand accent, ‘only just in time.’

I didn’t follow my first instinct and say that complaining about trains being late is a bit like complaining about the weather being wet and windy. ‘I think,’ I said, ‘that we’re awaiting permission to go along the branch line. When the signal at the end of the platform turns green, we’ve got it.’

The signal ahead of us was determinedly red. Another train arrived at the platform next to ours, on my right.

The warning played. ‘Mind the doors, please,’ thunk, the doors closed, and dit, dit, dit, daaah, the driver sounded the air horn. Our train began to move backwards.

The distant stars swung slowly across the sky, from right to left, as the train turned a curve. My heart rate fell back towards normal.

‘Driver speakin’ . My name is Malcolm. This is the Flyin’ Plutonium. We will be takin’ a diversionary route to Pluto and I expect to get there by about 42:00 Plutonious time.’

There was another outcry. Bloody hell, not again, bloody railways, bloody typical and so on. I heard myself mutter ‘Damn!’ under my breath, although I didn’t have to be on Pluto by any particular time. I wasn’t even sure how they reckoned the time of day on Pluto. Were the shops still open at 42:00? Were the buses still running? Did the taxis charge extra for being on night shift? Could you get roast beef, Yorkshire pudding and roast potatoes in a decent restaurant at 42:00? Was 42:00 day or night?

‘Driver speakin’. ’ Malcolm appeared to have heard every expletive, ‘Honestly, I’m sorry about the inconvenience but it’s better than running through the war zone and all being burned to ashes.’

Elegant Lady came back into the compartment. She must have heard the squaddies leaving the train. When she saw Trilby Hat sitting where her place had been, she asked me if she might sit next to me. I said, ‘Yes.’ When I smelled her perfume again,

‘I know it’s a trite thing to say,’ I said to her, ‘and it’s none of my business, but I’m sorry to hear about your brother. How old was he?’

‘I wasn’t troubled at all when I was dobbing them in,’ Elegant Lady said to me after a moment, ‘but now I’ve had time to calm down and think about it, I feel like a horrible, vindictive bitch.’

Clergyman stared at Elegant Lady. ‘Why did you do it?’

He picked his book up again. I saw the cover. The Elephant who Forgot where he Lived, by Malalai Hgulam.

I couldn’t resist asking what Chapter Eleven was about.

‘Fractal theory,’ he said, pianissimo.

Trilby Hat turned around and told us his name was Keanu and his wife’s name was Sheila.

‘Lunch time. Is anyone hungry?’ Stephanie appeared again with a pile of menus. ‘Your chance to try something seriously extra-terrestrial. Here.’ She put a handful of menus on the table. ‘The finest food from all around the solar system.’

Keanu asked, ‘Would it be all right if I chose something out of the middle of the menu first and then I ate something from the beginning of the menu after I finished it?’

‘One!’ Bam! ‘Two!’ Splat!’

Keanu devastated the two red buttons with punches that could have felled a mighty oak.

Sheila gasped. She didn’t think you had to hit them that hard. Keanu grinned at me.‘That’s the muscles you get from sheep shearin’ round the clock—’

There were two sudden bangs, like balloons bursting, as the grey plastic boxes exploded, each with the force of a stick of dynamite. It happened so suddenly that I didn’t even have time to hide under the table. When the smoke cleared, a layer of hot mouton parvenu was everywhere.

It was on my face, jacket, shirt and trousers.

It was splashed on the windows, it lay on the seats in puddles, it was on Evangeline’s dress and Sheila’s coat. It was splashed all over Keanu’s face. There was even some splashed on his hat.

‘Oh, my God.’ Stephanie handed us piles of paper napkins and we began to mop meat, gravy and carrots off ourselves and each other while Stephanie went to the spares cupboard to see whether there was any stock of seat covers.

Keanu picked the scrap of meat off the paper napkin, looked at it and ate it. ‘You’re right. That was 6085-W. I called her Ky-bosh. She was a fluffy little lamb with deep, big blue eyes and an enchanting habit of climbing onto a milk-churn, standing on one leg and pinging The Good Shepherd on the prongs of a grass-rake with the other three. She liked swimming in the billabong and begging lumps of sugar off the tourists. I remember one day in July when the circus was in town—’

Mercifully, Stephanie returned from the spares cupboard with an arm-ful of freshly laundered seat covers and began the job of taking all the be-splattered seat covers off and putting the clean ones on. ‘Do me a favour,’ she told Keanu, very amicably considering the circumstances, ‘When you want your two desserts, get cold ones. I’ve got a delicious

Two hours down, two hours to go. Corker lent the uncensored book to Evangeline, and she turned immediately to Chapter Eleven, excised from all recent editions. She was sitting beside me, saying little and concentrating on what the book said about fractal theory. ‘I have to learn this. I might never have another chance to read it.’

One of the two young ladies who, I had guessed, were students of French literature, or something similar, at one of the ancient universities, walked over to us. She was carrying a heavy and expensive camera.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, ‘I‘m Charlotte. I was hoping… Do either of you…,’ she seemed a bit doubtful, ‘Do either of you happen to know anything about cameras?’

I noticed that Evangeline had her fingers crossed as Charlotte walked back and gave the camera to Asher, who pointed it out of the rear window and took a couple of snaps of the stars that we were now heading away from. Evangeline uncrossed her fingers again when Asher called back, ‘Thanks, Joe, Evangeline, it works now.’

Charlotte walked back to us, looking enthused about something. She stared through the window. ‘Which one is Neptune?’

Charlotte pointed the camera and rattled off at least a dozen pictures of that one there, and then asked if I could see any other planets that might be Neptune.

‘Big, blue, lots of moons,’ I mused, staring at the dark sky and hoping to see a planet that ticked all the boxes. ‘No, sorry, that’s the only one I can see. What’s your interest in Neptune? Is it the most beautiful planet?’

There were a couple of brilliant flashes, and Joe sat with Charlotte and Asher to fill in the paperwork.

Stephanie came round with the trolley again and offered us tea or coffee. I had my usual cup of tea. Evangeline asked for the old railway stand-by, Viennese coffee. She took a sip, then another sip, and then she asked me if I’d ever tried Viennese coffee.

‘Can’t say I have,’ I said.

We were coasting now through the outskirts of the only city, slowing down as we approached the station. I had expected to find myself dwarfed among tall towers, skyscrapers, offices and massive apartment blocks, but — of course — having many times more land than they could build over in a hundred years, the pioneers had chosen to make the city from small buildings, low rise and open space. The sky was deep blue, the sun was small and weak and low in the sky, and the light on the city came from street lamps, windows, hoardings, signs and decorative illuminations.

‘Driver speakin’ We will arrive at Pluto in about five minutes. This train terminates here. All change, please. I apologise for the late arrival, which was due to civil conflict obstructing the main line at Neptune. When you leave the train, please make sure you take all your luggage with you. Have your ticket and passport ready for inspection. Please put your outdoor clothes on now, as the sun has only just risen and the weather is extremely cold. If you have a multi-planetary watch, please set it to Pluto. Plutonious time is 41:50 on Horusday, the seventeenth of Jove. Thank you for travelling Interplanetary.’

After Corker left the train, I noticed his book, The Elephant Who Forgot Where He Lived, lying on my table. Evangeline had been reading it, Corker had forgotten to ask for it back and she’d forgotten to give it to him. I picked it up, hoping to give it back to him. Perhaps I’d see him in the passport queue.

There was no passport queue. Nobody checked our tickets or our passports, perhaps because it was far too cold to stand out in the open for any length of time, or perhaps because somebody trusted us. Evangeline had put on what appeared to be a heavy fur coat and a hat to match. I only had a Kerberry overcoat, sufficient for the British winter but hopelessly inadequate out here in these parts. ‘I hope it isn’t far to the hotel,’ I said through chattering teeth.

There was a coin-in-the-slot telescope near the exit, inscribed See Earth From Afar.

‘Do you want to see where you came from?’ said Evangeline.

I put the coin into the slot and the scope swung around and pointed itself in exactly the right direction. In the cross-hairs of the eyepiece I saw the Earth, three billion miles distant, and I suddenly realised the enormity of the journey I had just made and how upset I would be if I couldn’t get back.

We walked through the station concourse, dodging the little two seater car that was slowly coming towards us, following a coloured strip laid on the floor, and honking its horn, and we came out onto the street. The city had been built to cope with constant cold and near darkness. On the planet where last summer might have been more than a century in the past, lights picked out every edge that you might fall over. Warm air from grilles in the pavements meant that so long as you kept to the streets, and so long as you wore a hat, overcoat and gloves, you could take a short walk in the open air without being frost-bitten.

‘That’s the Galactic, there.’ Evangeline pointed to a brightly lit, square concrete blockhouse on the opposite side of the road.

Evangeline handed them over. Kevin held them up to a lens on the desk. Her credit card lit the green light. The passport didn’t. Neither did mine. ‘I’m sorry,’ said Kevin, ‘I have to ask you whether you showed your passport at the railway station.’

He gave us back our passports.

‘All right,’ I said, ‘we’ll be back. Which way is the Police Station?’

We took a seat. ‘Are you really offering to share a room with me?’ I asked as quietly as I could.

A ping sounded, like a bicycle bell, and a sign lit up on the wall behind Kevin’s desk. Minic for Webb to Police Station. Stand clear, please.

We piled our luggage behind the seats of the car and sat down. The car drove us along the city streets for five minutes.

When it stopped, a policeman opened the doors. ‘I’m Constable Weaver. Webb and Johnson, passport problem, right?’

At the front desk, a policewoman asked us for our tickets and passports. She typed something on a keyboard and read a message that appeared. ‘Mrs Webb, you’re free to go. Mr Johnson, there’s something we need to discuss with you. We need to detain you. You may send a telegram of twelve words to any address on Earth.’

Constable Weaver led me down some steps and put me into a cell.

‘What’s happened?’ I asked.

It was a very small cell, perhaps six feet from end to end, just long enough for a bunk bed, and four feet wide, if that. I took my outer clothes off, lay on the bunk and pulled the blanket over myself.

A minute passed, maybe two.

Without knocking, another man, dressed in a black uniform and a peaked cap, carrying a wooden tray, opened the cell door and said, ‘Good morning, Mr Johnson. It’s seven forty-five.’ He put the tray down on the bedside table, which I hadn’t noticed before. ‘I’ve brought ye a continental breakfast and a pot of tea. Ye can get a cooked breakfast in the North British Hotel. Could ye please make sure that ye’re away off the train by half past eight.’

‘Tell me something I don’t know,’ I thought.

‘I expect to get you into Uranus in seven and three-quarter hours, at about 12:20 Uranious time. There will now be a ticket and passport check. Please check that you have a ticket and a passport. If you haven’t got a ticket or a passport, tell Dave, the Senior Conductor, and he’ll tell you exactly what you can do. Thank you.’

‘Good idea. Just what I was thinking.’

I looked at her and said, ‘Hello.’

‘Hello, sir! I’m Stephanie, I’m the chef.’

‘You’re most welcome,’ I said. ‘I’m Ken. I’m a passenger. It looks as though you’re the waitress as well.’

‘They let me out of the galley every couple of days.’

‘Do you ever think that you might escape one day?’ I asked.

‘No,’ she said. ‘They chain my ankle to the microwave.’

‘Despite being the product of captive labour, this looks a very appetising snack,’ I said.

‘Good,’ she said, nodding. ‘I made it specially. Mark you, everything looks better in a plastic box.’

I picked it up to open it. ’It’s cold.‘

’Press the red button on the lid, sir.‘

’This one here?‘ I pointed to it, and Stephanie nodded., so I pressed it gingerly. There was a brief noise of bubbling and hissing. ’Oh, that is hot.‘

‘Take care,’ said Stephanie, ‘it’s hot,’ and waving her hand over the bottles, she added, ‘Do you want one of these?’

‘That’s all right,’ he said beatifically, ‘just leave the caps on the table by accident. One cap would do.’

‘I’m honestly sorry, sir,’ Stephanie apologised, ‘but I can’t do that either, because they always count the caps before they let me go home.’

‘It’s just as well I brought a cork with me, then,’ he smirked, and Stephanie moved on.

One of the soldiers that I’d seen on the platform in Parkway, a short, pale man of twenty or twenty-five, with curly red hair and freckles and dressed in Army camouflage, put his head into the compartment and asked, ‘Is the ticket inspector in here?’

One of the soldiers that I’d seen on the platform in Parkway, a short, pale man of twenty or twenty-five, with curly red hair and freckles and dressed in Army camouflage, put his head into the compartment and asked, ‘Is the ticket inspector in here?’

‘No.’ I fell for it. ‘Nobody’s looked at our tickets.’

The soldier turned and said to somebody behind him, ‘There’s three empty seats here.’

Ginger Squaddie hesitated, ‘All right.’ He put the cigarettes back in his pocket.

‘Thank you,’ said Clergyman. He swallowed some of the whisky, picked his book up again and immersed himself back in it. It looked like a well worn tome which someone had found lying around in a Salvation Army shop, paid sixpence for and then given to Clergyman when he discovered it was so boring that he couldn’t read it.

‘It’s a pity Mike isn’t here, sir,’ said one of the two, in a dense Glasgow accent.

‘Yes, Private McGovan,’ Ginger Squaddie replied. ‘You might not have heard. I’m sorry to tell you that he was blown up by a bomb.’

‘Well, he shouldnt’ve been plantin’ it.’ Like Ginger Squaddie, the third of the soldiers spoke East London. ‘I told ’im, Mike, those fings are dangerous. You stay away from ’em.’

Private McGovan shook his head sadly. ‘The silly fool.’

‘Yomp across endless miles of frozen methane and shoot people. It’s what we’re good at.’

‘Do they really need us, sir? Can’t they shoot each other without us?’

‘There’s more to it than that. When we reach Neptune our mission will probably be to bring the civil war to a peaceful end. I’m only guessing.’

‘You mean, we’re engaged to perform the vital rôle of cannon fodder.’

‘Yes. Only please remember to call it peace-keeping.

I haven’t had my orders yet, so don’t either of you yomp anywhere until I tell you.’

‘Sir.’

‘The Kingdom of East Bog-hole, I think. They’re the ones that we let into the British Empire. They have lithium mines and underground reservoirs of ytterbium, all of which they are happy to swap for half a stone of conch shells and hama beads. So I guess the plan is to defeat the Egalitarian Republic of West Bog-hole.’

‘ ’Scuse me?’

‘I guess,’ Ginger Squaddie emphasised the word, ‘the plan is to defeat the Egalitarian Republic of West Bog-hole.’

‘That’s a plan?’

‘If the Peace Office says it’s a plan, Private McGovan, then it’s a plan. But I haven’t had my orders yet and anything could happen.’

‘That’s because we were wearin’ camouflage,’ said Ginger Squaddie.

‘Do you lads want something to eat?’

‘We ’ad eggs and bacon in the NAAFI before we set off, but a couple of beers would be nice.’

‘Apart from Nathan there,’ said McGovan, looking at East London Squaddie, ‘ ’e ’ad cornflakes ’cause ’e’s a wuss.’

Stephanie took one of the bottles off the trolley. ‘I’ve got Imperial Splendid Ale, 6%?’

‘That’ll do nicely.’

McGovan stared mournfully at his bottles of Imperial Splendid and said, ‘Waste of a young life. Soon as I saw ’im walkin’ down the Plumstead Road carryin’ it, I thought, ’e shouldnt’ve been muckin’ about with bombs. ’E could just’ve gone in and bought the damned television.’

‘That’s right. That’s where he was goin’— ’

‘That was my brother’s shop! He was working there. Your mate blew my brother to pieces!’

Ginger Squaddie made an ill fated attempt to calm things down. ‘Horrible things happen in wars, miss— ’

Elegant Lady screamed and punched Ginger Squaddie in the face. Blood poured onto his camouflage shirt. ‘There isn’t a war on the Plumstead Road, you idiot! If you couldn’t stop the man all by yourself, why didn’t you tell someone who could? You must have phones in the barracks…’ She paused briefly,

‘My brother’s dead,’ said Elegant Lady, beginning to weep, ‘because these men didn’t do anything.’

‘I think you and I need to talk,’ said Dave, ‘just to get things straight.’

‘Thank you,’ said Ginger Squaddie, clutching the paper to his broken nose. ‘I need to get cleaned up before—’

My trainspotter’s instincts

told me something was about to happen that wasn’t in the timetable. Our driver got out of the cab, taking the key with him.

My trainspotter’s instincts

told me something was about to happen that wasn’t in the timetable. Our driver got out of the cab, taking the key with him.

Those electric departure boards above the platform that usually would have said, ‘Pluto, calling at Neptune,’ said instead, ‘Pluto, non stop.’ I had been staring at the signs and watching the passengers joining and leaving the train for a minute or two before the explanation came.

Those electric departure boards above the platform that usually would have said, ‘Pluto, calling at Neptune,’ said instead, ‘Pluto, non stop.’ I had been staring at the signs and watching the passengers joining and leaving the train for a minute or two before the explanation came.

‘Sir.’

‘Brigadier Clarke, Second Atom Bomb Brigade, at your service. The Army needs you on Neptune. I’ve arranged transport for you to the combat zone. Get your kit, check your identity disks and your ammunition, and quick march to the over-bridge on the right — and keep well clear of the bushy-topped animals. There’s an armoured personnel carrier waiting for you.’ He looked around at us other passengers. ‘Whoever sent the telegram to HQ, thank you. It must have cost a fortune. I could never have found them otherwise.’ He smiled for the first time. ‘Proper buggered up my game of golf, this shower has.’

I pointed to the seats where Elegant Lady and her handbag had been sitting. ‘I think those are empty, there.’

‘Excuse me sticking my nose in,’ I said, ‘but you do know this train is going straight to Pluto?’

‘No,’ said Trilby Hat, ‘but if you sing the verses, I’ll join in the chorus.’ Hehad obviously been waiting for months to reply to my question or a similar one,

‘Oh, yes,’ said Bobble Hat, not laughing, ‘they already told us that.’

‘And they also told us,’ Trilby Hat sounded quite annoyed, ‘that the train’s half an hour late already. Have you any idea what’s going on?’

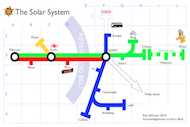

Author’s note: This diagram shows what is going on.

This diagram shows the train movements that happen at

Uranus Station. My train is the first one to enter the station.

I noticed that our driver had not returned to the driving seat.‘Dave! Dave!’ I was a bit panicked. ‘There’s nobody driving the god-damned train!’

‘Malcolm’s driving it from in front,’ said Dave, who must have heard me in the next carriage and rushed in to make sure I wasn’t hammering on the emergency stop button. ‘We’re going backwards. The back-end cab’s my office for the duration.’

which definitely wasn’t the sort you could buy at your local supermarket beauty counter for two pounds fifty, I felt quite privileged.

which definitely wasn’t the sort you could buy at your local supermarket beauty counter for two pounds fifty, I felt quite privileged.

‘Older than me,’ she said, ‘but those three’ll pay for their sins of omission. They’ve been sent to the war zone.’

‘Weren’t they going there anyway?’

‘No, they weren’t,’ Elegant Lady told me. ‘The corporal was having them on. They were going there to guard the British Embassy. I could see their gate-passes tucked in his wallet. A cushy number. Three meals a day and a comfortable bed every night in exchange for standing still and holding a drill rifle. They won’t get that in the war zone.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes. I once had a fifth-tier job in the Diplomatic Service. I saw dozens of gate-passses.’

‘So what did you tell the Peace Office?’ I asked.

‘Only that I thought I’d seen the three squaddies they were looking for.’

‘Death and destruction all around I see,’ quoth Clergyman. He was still looking into his book, and was probably reading it aloud without realising it.

Clergyman looked up as if she’d been talking to him. ‘It doesn’t have to be like that,’ he said.

Elegant Lady lost her temper. ‘Yes, it bloody well does,’ she hollered back at him.

‘Why did I send a telegram to the Peace Office?’ Elegant Lady repeated. She thought for a moment.‘Revenge, I suppose. They sat and watched while their mate killed my brother. They’ve been packed off to the war zone.’

‘They probably won’t come back,’ said Clergyman, sagely.

‘I suppose I ought to regret bitterly what I did in a moment of real anger,’ she told him, ‘but I don’t. ’

Clergyman was quiet, probably weighing his words. I put my oar in. ‘There wouldn’t have been much point in having them put on trial. The culprit died in the explosion. No point trying him in absentia and sending his mortal remains to the glasshouse. The ones we saw were just spectators.’

Clergyman seemed to be avoiding an argument. ‘Yes. I suppose you’re right about that.’

‘Isn’t that the same woman,’ I asked without thinking, ‘who wrote There’s Water in my Soup?’

‘Who?’ Clergyman asked me.

‘Hgulam. That book you’re reading.’

‘Yes,’ he told me, ‘Brilliant, isn’t she. I think I’ve read everything she ever wrote. This one’s only been printed in a censored edition for years, but a parishioner found an older edition in a charity shop with Chapter Eleven still all there, and she bought it for sixpence and gave it to me.’

‘Sixpence?’ I asked.

‘Sixpence, yes. We’re rather an old-fashioned parish.’

‘Why would anyone—’

‘Everyone asks that,’ said Clergyman, lowering his voice to the barely audible. ‘Fractal theory says that two people can have different answers to the same problem, both be right and both able to show that the other person’s answer is wrong. You can imagine how that upsets people like Liz Truss, I hope. For instance, what is the distance from—’

‘It’d probably be best if we didn’t discuss it where people might hear us,’ said Elegant Lady.

‘You’re right,’ I said. ‘There’s no point taking an unnecessary risk.’

‘My name’s Evangeline, by the way,’ she added. ‘Let’s be friends.’

‘Ken.’

‘I’m Corker,’ said Clergyman, ‘short for Reverend McCorquodale.’ He held his hand out and Evangeline shook it delicately.

‘Why do you keep telling people that my name’s Sheila?’ asked Sheila.

‘Because it is Sheila,’ Keanu explained.

‘Did you say you read There’s Water in my Soup? I read it when it came out. Our daughter bought it for me as a birthday present. Couldn’t make head nor tail of it. Why couldn’t the woman just say what she had to say and then shut up?’

‘The first chapter isn’t the easiest.’ Corker spoke with all the authority and confidence of a literature counsellor. ‘You can start in the middle and read the beginning later. You’ll probably be able to make sense of it—’

‘Hey, what is this?’ asked Keanu. ‘Are you a literature counsellor, or something?’

‘Well, yes, as a matter of fact—’

‘No,’ said Stephanie, ‘I’ll get confused and it won’t taste right, but you can have two desserts if you want provided you ask for them in alphabetical order.’

‘Sounds good to me.’ Keanu glanced at the menu without reading it. ‘Give me mouton parvenu.’

‘Here you are.’ Stephanie put a grey plastic box on the table in front of him. ‘Madam?’

‘Oh, er…,’ Madam took the coward’s way out. ‘Give me what he’s having.’

‘Sure.’ Stephanie put a second grey box in front of Sheila.

Sheila put her hand on her grey plastic box. She looked concerned. Then she put her other hand on Keanu’s grey plastic box. ‘Hey — they’re both stone cold.’

‘They’re in thermal packaging. Press the red button on the lid.’

Keanu asked his wife, ‘May I do that for you?’

‘Sure,’ said Sheila, who had probably not imagined what was likely to happen as a result. ‘Go ahead, give it a good thump.’

‘I just realised something,’ I said to Keanu, as I picked a piece of meat the size of a stock cube off my tie and wiped it onto a paper napkin, ‘This is sheep meat. You’re from New Zealand so you must be a sheep farmer.’

‘ ’S right,’ Keanu nodded, ‘I am.’

‘You’ve probably known this poor woolly soul since the day it was born.’

‘Ah, shut up,’ said Sheila, ‘you’ll make me burst into tears in a minute.’

‘What?’ Keanu looked incredulous. ‘Burst into tears? I don’t believe it. You were the one who drove Ky-bosh onto the pick-up truck with an electric cattle prod, tied her up and drove her to the slaughterhouse. She was crying and holding on to the barn in a desperate effort—’

Sheila began, ‘I bloody never did,’ before Keanu burst out laughing.

‘Once you’ve learned it, they can’t take it away from you,’ I said, trying to be supportive. Inside, I hoped that a conversation would break out between us, but I said, ‘Take the chance while you have it.’

Evangeline looked up. ‘Well, I used to be a model, so I’ve seen a fair few. What’s the problem?’

‘It doesn’t work.’ Charlotte handed the camera to Evangeline, who turned it around and took a long look at it. If she’d had a magnifying glass, she would have taken it out of her handbag and examined the camera through it.

After a minute, she recognised it. ‘Top of the range Eagle Eye Two. I’ve stood in front of one of these often enough. Fur coat, cashmere scarf, six-inch heels, you name it. For clothing catalogues, I have to add. I wasn’t a lonely heart.’

‘So, er,’ Charlotte continued, ‘can you fix it?’

‘I don’t know, but let’s be optimistic until proven otherwise.’ Evangeline up-ended the camera and stared at its controls. ‘I must’ve learned something from all that standing about and watching the birdie.’ She turned the camera over again. ‘Where do you switch it on?’

‘Here. The light is supposed to go on.’

Evangeline pressed the button, and nothing happened. ‘Flat batteries.’

‘Asher!’ Charlotte called to her fellow passenger. ‘Didn’t you change the batteries?’

The man with the black leather jacket and the large camera case walked over to us. ‘Can I help? Joe Bloggs, from The Sun’ He held up his Press card, which had his photograph but said he was Lawrence Twigg from the News of the Earth. He took the camera out of Charlotte's hands without asking, and flipped the battery cover open. ‘One of the batteries is the wrong way around.’

‘Oh, wow,’ Charlotte sighed, ‘I do feel dim.’

Joe turned the misplaced battery around, closed the back, and took a photograph of Evangeline. The camera worked properly.

‘Is it all right if I take your photograph?’

‘For ten per cent,’ Evangeline smiled. ‘Send five pounds to the agency.’

‘Of course. You were Janice Holmes when I last met you, weren’t you? Stage name?’

‘You have a good memory.’

‘You sort of stuck in my brain,’ said Joe. ‘The Sun will pay fifty quid for a picture of you on the train.’

‘Tell me,’ I said to Charlotte, ‘a news photographer needs a camera the size of shoe-box, maybe even a wedding photographer, but is there a reason why you’re carrying such a big camera? Is it to do with your studies?’

‘We decided we want to be photographers when we grow up.’

‘A wise decision, madame.’ Evangeline observed. ‘You’ll be on the side of the camera that the money comes out of.’

‘Asher might. She’s the one with business sense. I couldn’t organise a snail sandwich in a room full of French chefs de cuisine. Let me try this camera out.’

I looked out of the window, trying to remember something of the astronomy programmes that I used to watch years ago, sitting in front of the hearth at tea-time. In my mind’s ear I heard Patrick Moore saying that Neptune is a giant planet, dark blue in colour and has lots of moons. I pointed through the window to a planet that appeared to be dark blue, lay ahead of us and might have had lots of moons, although I couldn’t see any, ‘Maybe that one there?’

‘I want to be a war photographer when I graduate,’ said Charlotte, ‘and this is as close to a war as I’m likely to get before term starts.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ said Evangeline.

‘You’ll need a powerful tele-photo lens,’ I observed, ‘at this distance.’

‘I have one,’ said Charlotte.

Joe popped up again with a lightweight hand-size. ‘May I take a couple of pictures of you and your friend?’Charlotte and Asher… Could you just sit over there?

‘’Sure, why not?

‘Look into the camera, say cheese…’

‘Your hotel might serve it, if you ask them nicely. Which hotel are you staying at?’ she asked.

‘I hadn’t thought about that,’ I admitted, ‘I haven’t reserved anywhere.’

‘I’m staying at the Galactic. You could stay there. We might bump into each other.’

Suddenly I was wide awake. ‘Are you saying what I think you might be saying?’

‘That depends on what you think I might be saying.’ Evangeline smiled. ‘When we arrive in Pluto, I’ll show you where the Galactic is, and you can decide.’

‘About five minutes,’ Evangeline said, reassuringly. ‘Do you want to look back?’

‘Does it take British credit cards?’ I asked.

‘No, you need a 2

‘Can you really read that language?’

‘Punjas. Yes, eveyone who works in the fifth tier has to know some languages. I chose French and Punjas.’

Evangeline led me to the reception desk, where a young man in a cheap grey blazer and a short back and sides smiled at us from behind a name card. Kevin. ‘Good morning, afternoon, whatever it is. I’m Evangeline Webb. You should have a reservation for me.’

‘Yes, I have. Room C-25, is that okay?’ Evangeline nodded thoughtfully, turned and whispered to me, ‘Do you want to share?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘Very much.’

‘I need to see both your passports and a money card,’ said Kevin.

‘No, we didn’t,’ said Evangeline.

‘Nobody asked us for our passports,’ I added.

‘I regret the inconvenience,’ said Kevin, ‘but you’ll both have to go to the Police Station and show your passports and return tickets. The computer thinks that you might’ve entered the planet illegally.’

‘I’ll call a Minic. It’ll come in here and pick you up.’ He pointed to a coloured strip on the floor. ‘It’ll know where to take you. Have a seat. Don’t worry, it happens often. Just a formality.’

‘Yes.’ Evangeline looked at me and smiled. ‘You see? I really was thinking what you thought I might be thinking.’

There’s a first time for everything, I thought.

‘Just go and sit in it,’ said Kevin. ‘Everything else is automatic.’

‘Yes, Officer,’ said Evangeline, ‘I’m Webb and he’s Johnson.’

‘Fine, don’t worry about a thing. We’ll soon sort this out.’

‘I want to send it to Evangeline Webb at the Galactica Hotel.’

‘Of course. What do you want to say.’

I dictated the text. ‘I may be some time at the Police Station. See you later.’

‘Twelve words exactly. I’ll send that for you.’

‘We found something in your luggage,’ he said, ‘that’s of interest to us.’

They’d found that book. Damn! God alone knew what would happen to me now. Three billion miles suddenly seemed an awfully long way.

‘Can you give me any idea of how long I’m likely to be here?’

‘Well, at least until the day shift arrives. Three hours or so. You should make yourself comfortable. If you need anything, anything at all, we haven’t got any.’ He walked out into the corridor and locked my door behind him, making a deliberate grating noise.

‘Who are you? Where is Evangeline? Where am I?’

‘Ye’re in Edinburgh Waverley, sir.

Ye’re on board the Night Scotsman.

I think maybe ye’ve been dreaming.’